Kenneth John Conant (1894-1984)

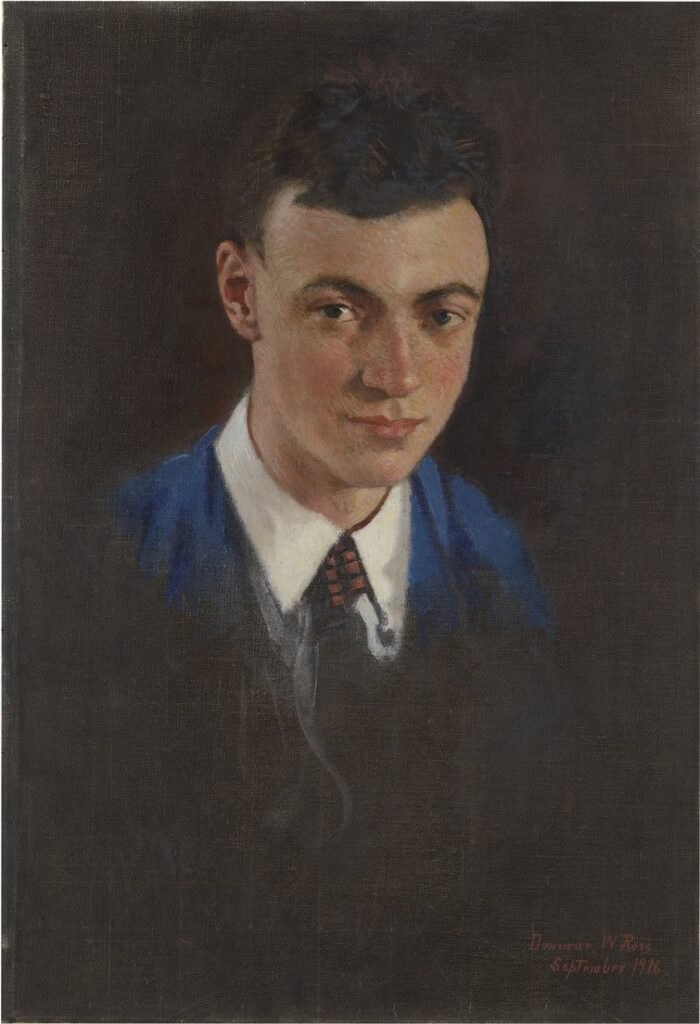

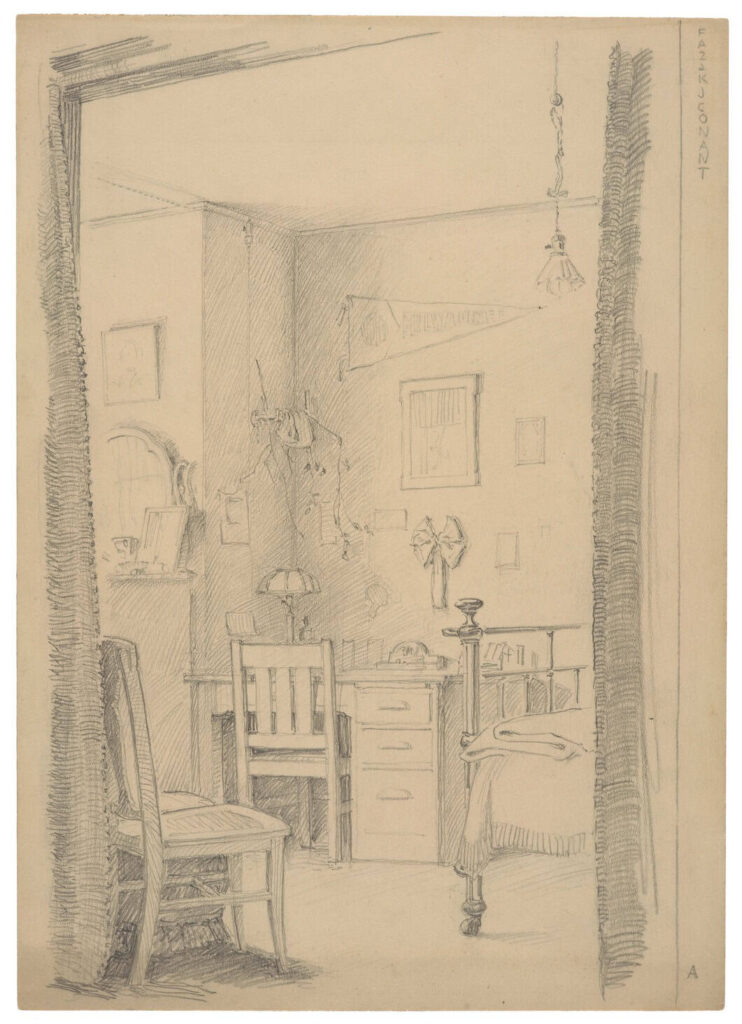

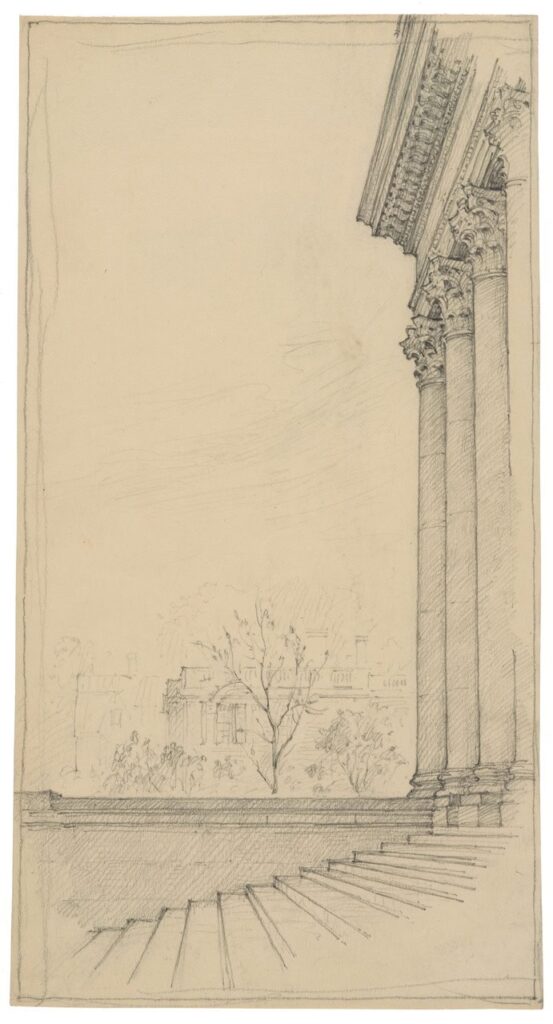

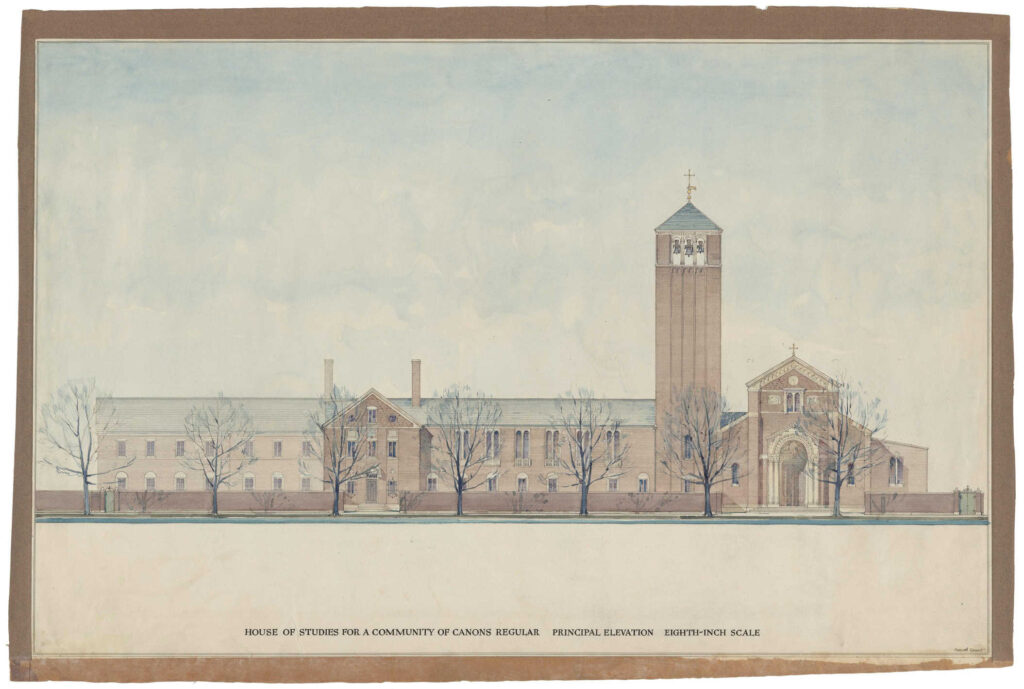

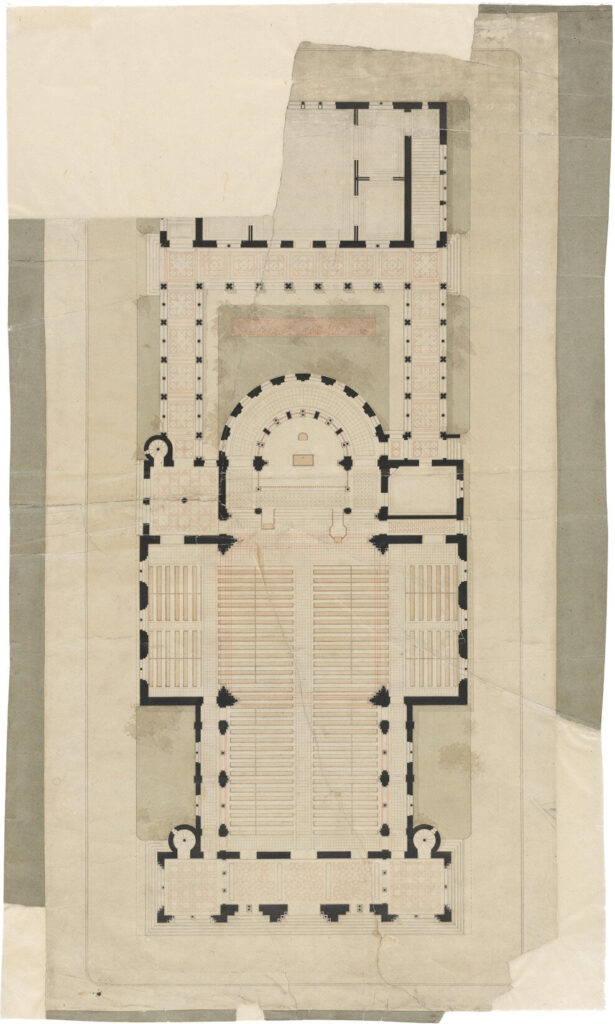

Kenneth Conant, having received his B.A. from Harvard College in 1915, enrolled in Harvard’s recently-founded (1914) graduate school of architecture. An oil portrait by Denman Ross, perhaps his teacher of art and design theory, shows the young man in his first year of graduate study (fig. 1). Conant’s drawing assignments for Fine Arts 2a from about this same time, depict a Harvard dorm room and the just-completed steps and Classical Order of Widener Library’s facade, which had opened to the public in June of 1915 (figs. 2, 3). These drawings attest to Conant’s extraordinarily power of observation and imaginative composition. A fellowship for study at the École des Chartes and the École du Louvre took him to Paris in 1916; when the United States entered World War I in 1917, Conant enlisted. He received his MArch in 1919 – it was delayed because of his service in World War I — with a thesis project for a monastery in Cambridge, Massachusetts (figs. 4, 5, and 6). Conant worked briefly for fellow architect and Harvard graduate William Graves Perry, a founder of today’s Perry Dean Rogers Partners Architects, and talked about projects with Ralph Adams Cram. Designed in the Romanesque style, Conant’s thesis project anticipated the monastic complex (now the guesthouse) built by Cram some four years later for the Society of Saint John the Evangelist (the Episcopal Cowley Fathers) on Memorial Drive in Cambridge (fig. 7). It was during conversations between Conant and Cram about this monastery project that its patroness, Isabella Stewart Gardner, insisted Conant be baptized in the Episcopal Church and offered herself as sponsor. In 1920 Conant was hired as an instructor in architectural design at the Harvard Graduate School of Architecture. Promoted to assistant professor in 1925 and full professor in 1936, he taught studio and lecture courses at Harvard until retiring in 1954.

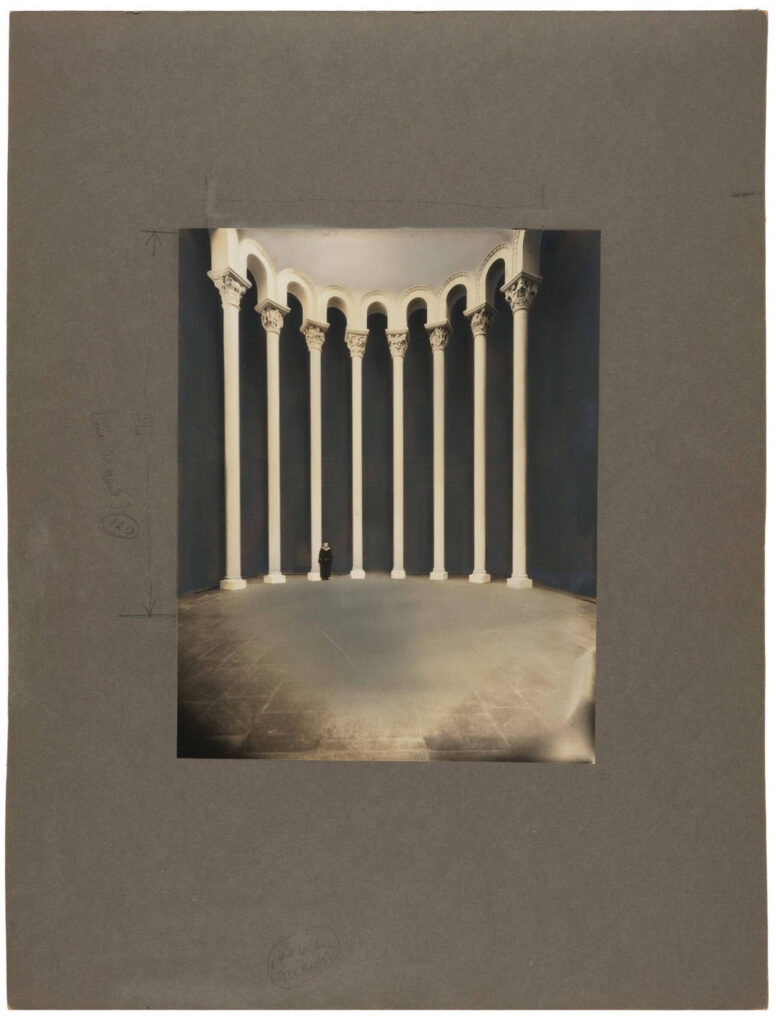

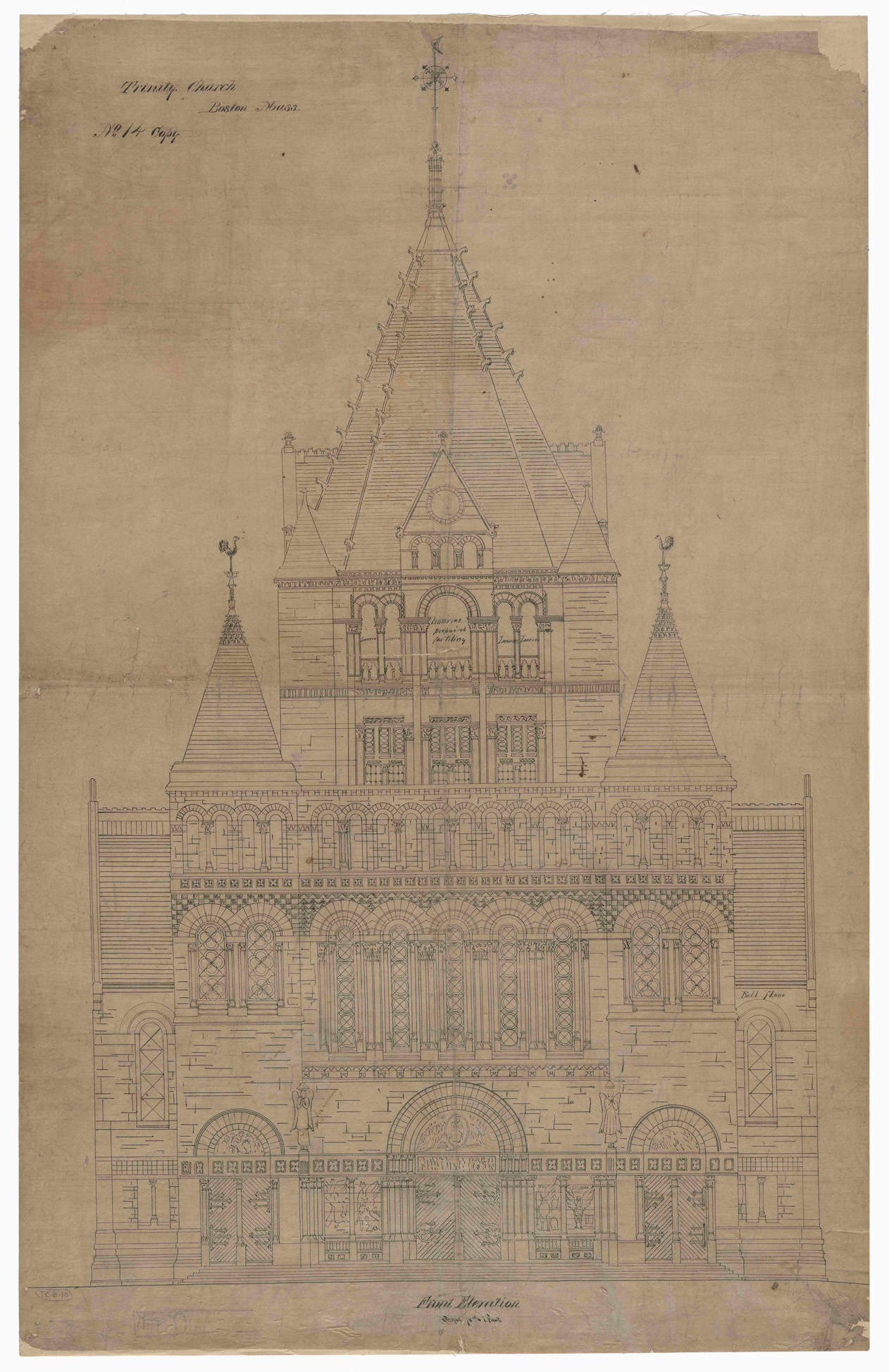

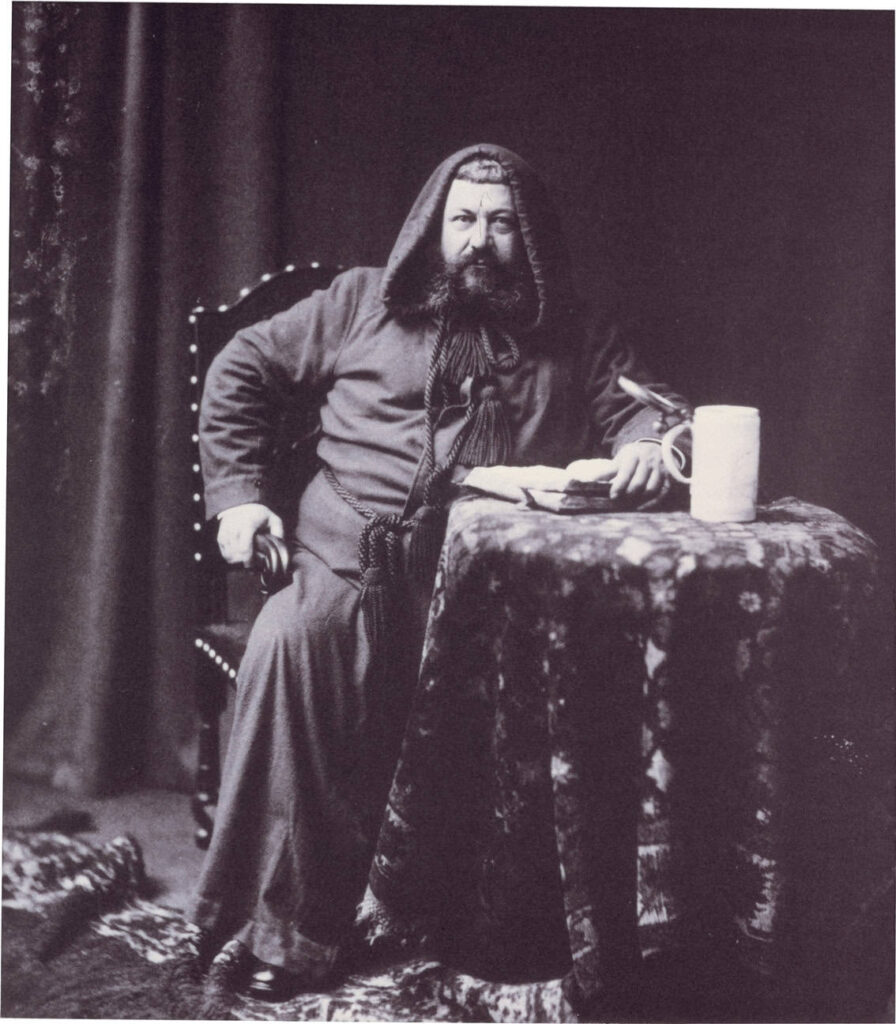

That the young Conant was aware of and attracted to the Romanesque style might seem surprising at a time when the Gothic Revival was so popular in the United States, but Boston – and Harvard – were exceptions. Boston was home to Henry Hobson Richardson’s Romanesque Revival, exemplified by his commission for prominent Episcopalians, Trinity Church (1877), located on Copley Square in the new Back Bay neighborhood of Boston (fig. 9). That Richardson, himself a Harvard graduate, chose to wear a kind of monk’s habit for his portrait by George Collins Cox (fig. 8) foreshadows Conant and Cram’s association of monasticism with Romanesque architecture, an association influential both for Conant’s own later idealization of Cluny and for his self- representation in quasi-monastic garb (his academic gown) in the Fogg Museum reconstruction of that abbey church (fig. 100).

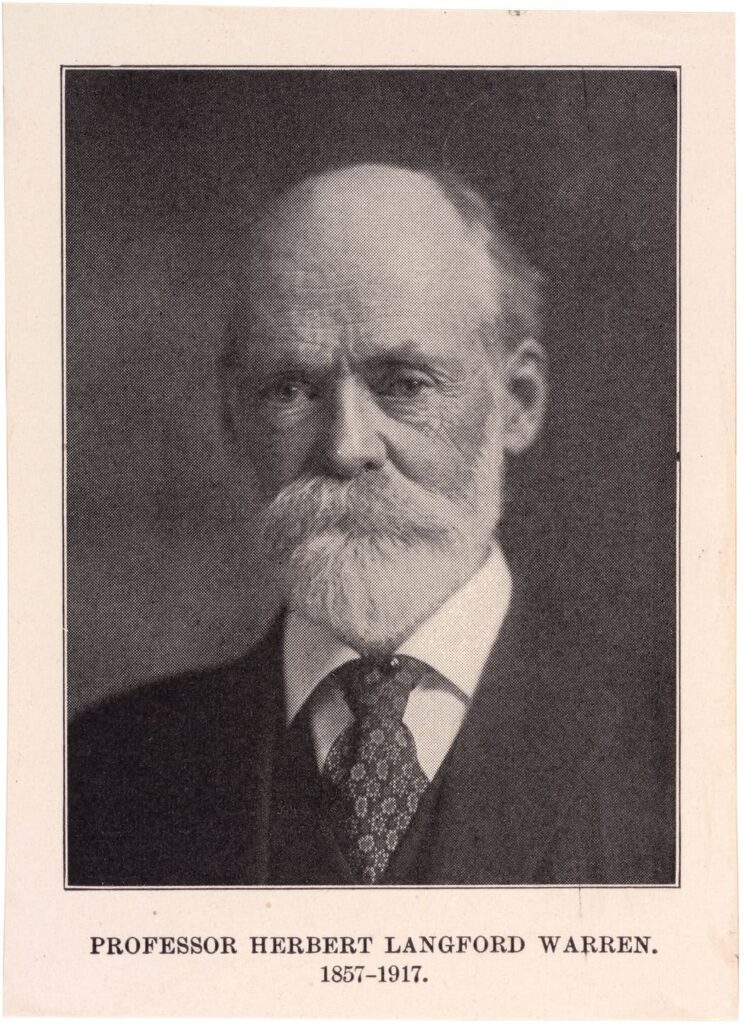

Herbert Langford Warren (1857- 1917) (fig. 10), dean of the Graduate School of Architecture when Conant studied there, had worked in Richardson’s office, was president of the Society for Arts and Crafts (founded in Boston in 1897), and taught a course in medieval architectural history at Harvard which Conant would have taken. Indeed, a medieval survey course first given in 1896 has been offered continuously from then until now. Warren himself worked in several different styles – Romanesque, Gothic, and Renaissance, — as well as providing the illustrations for Morris Hickey Morgan’s English translation of Vitruvius (1914). A charming example of Warren’s design is adjacent to the Graduate School of Design, the Church of the New Jerusalem, also called the Swedenborgian Chapel (1901) (fig. 11).

Henry Hobson Richardson (1838–1886)

Trinity Church, Boston. View of east end and north transept

Harvard Fine Arts Library, Digital Images and Slides Collection, 1975.03000 182 B657 2TE

George Collins Cox (1851–1902)

Henry Hobson Richardson in a monk’s habit Harvard Fine Arts Library, Digital Images and Slides Collection, 1975.02995

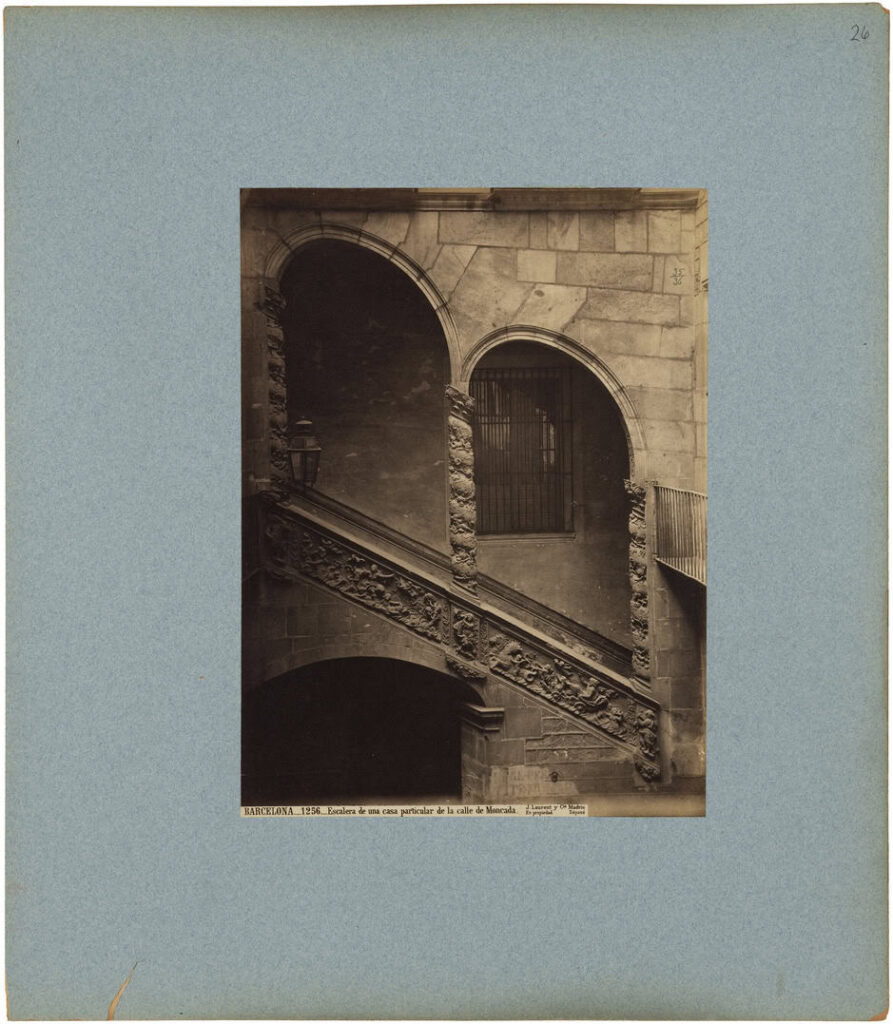

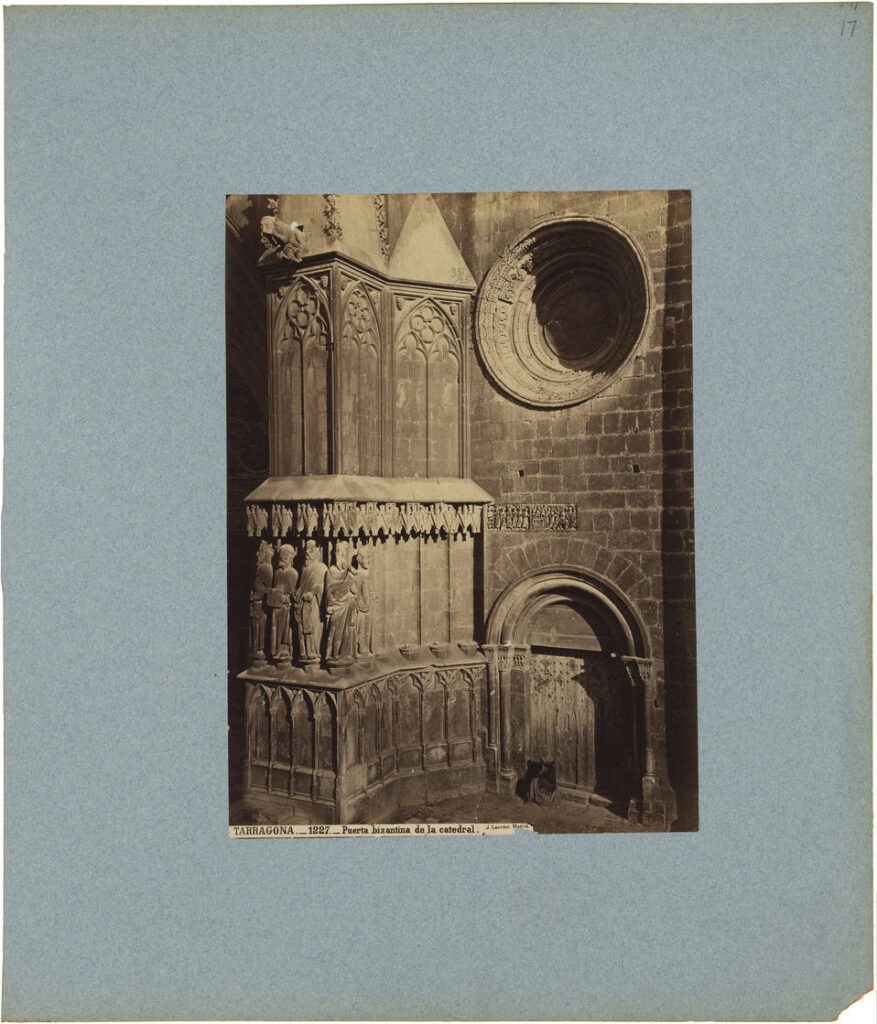

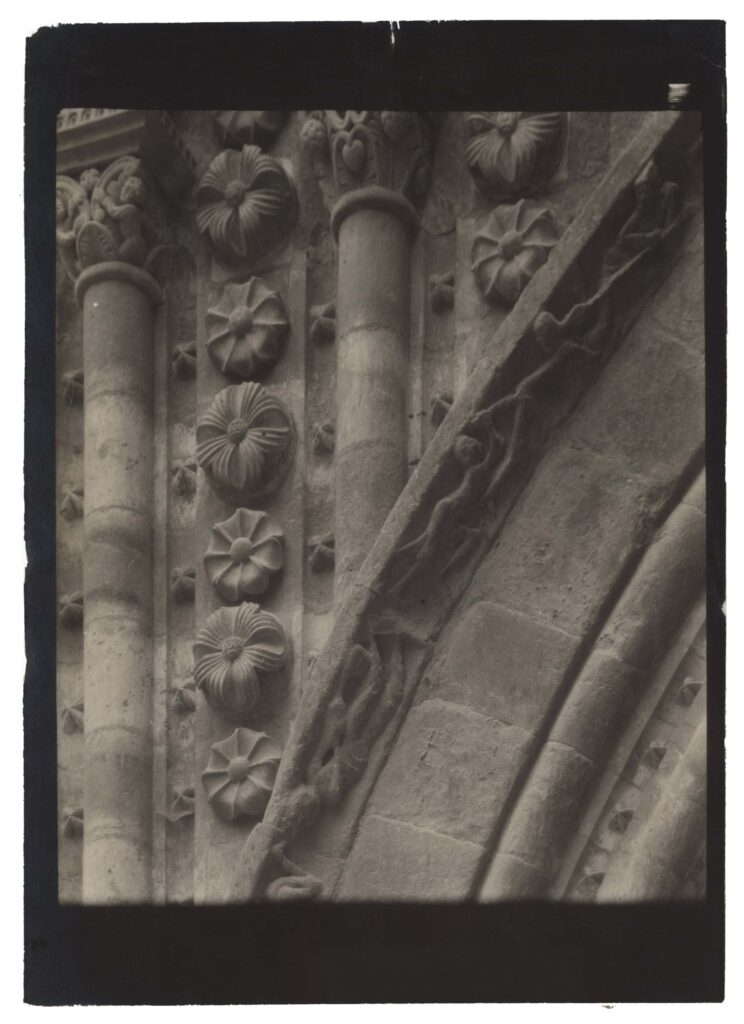

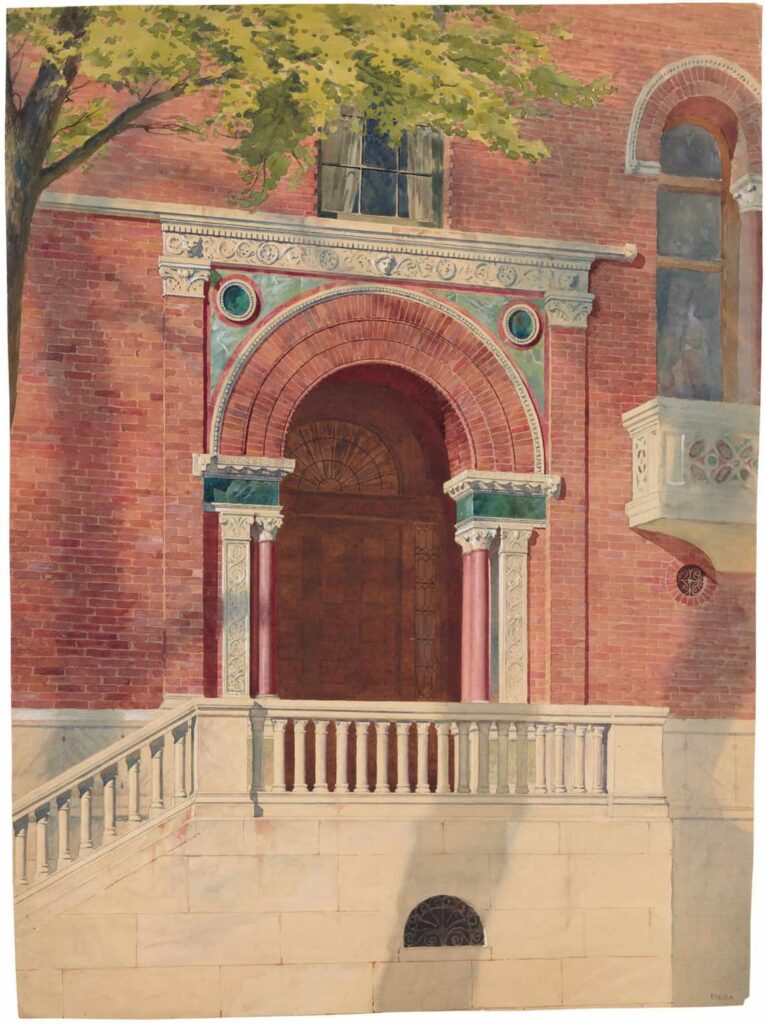

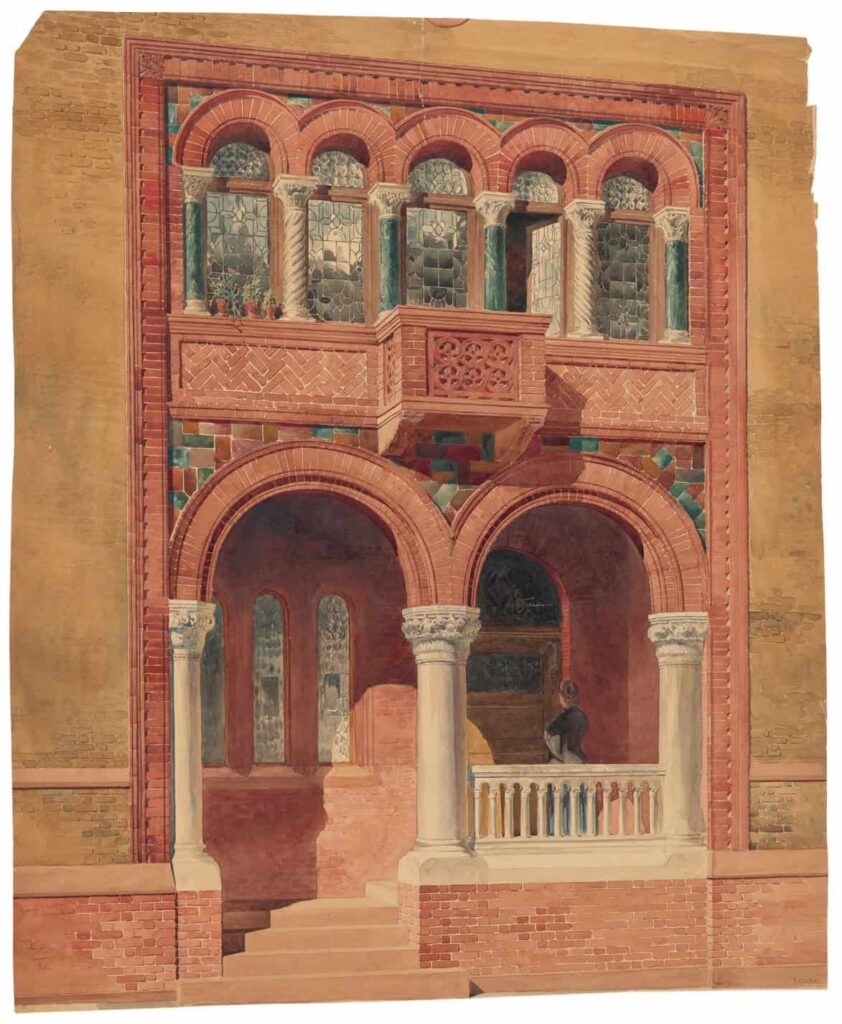

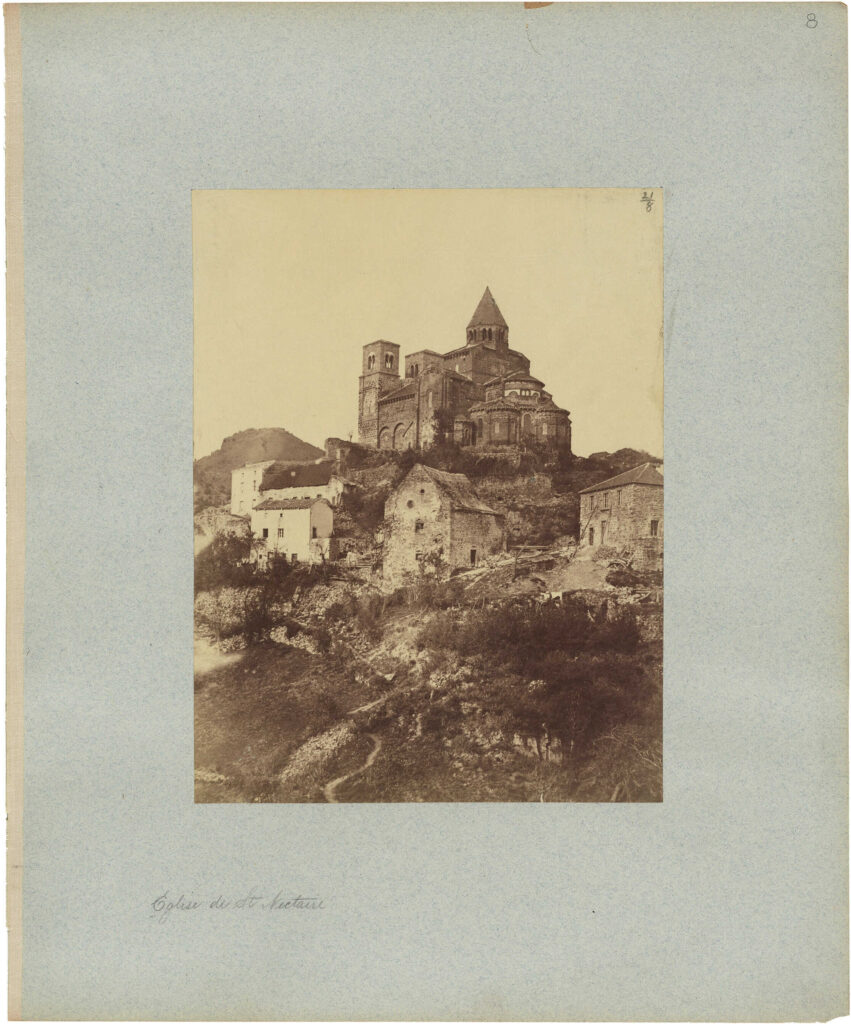

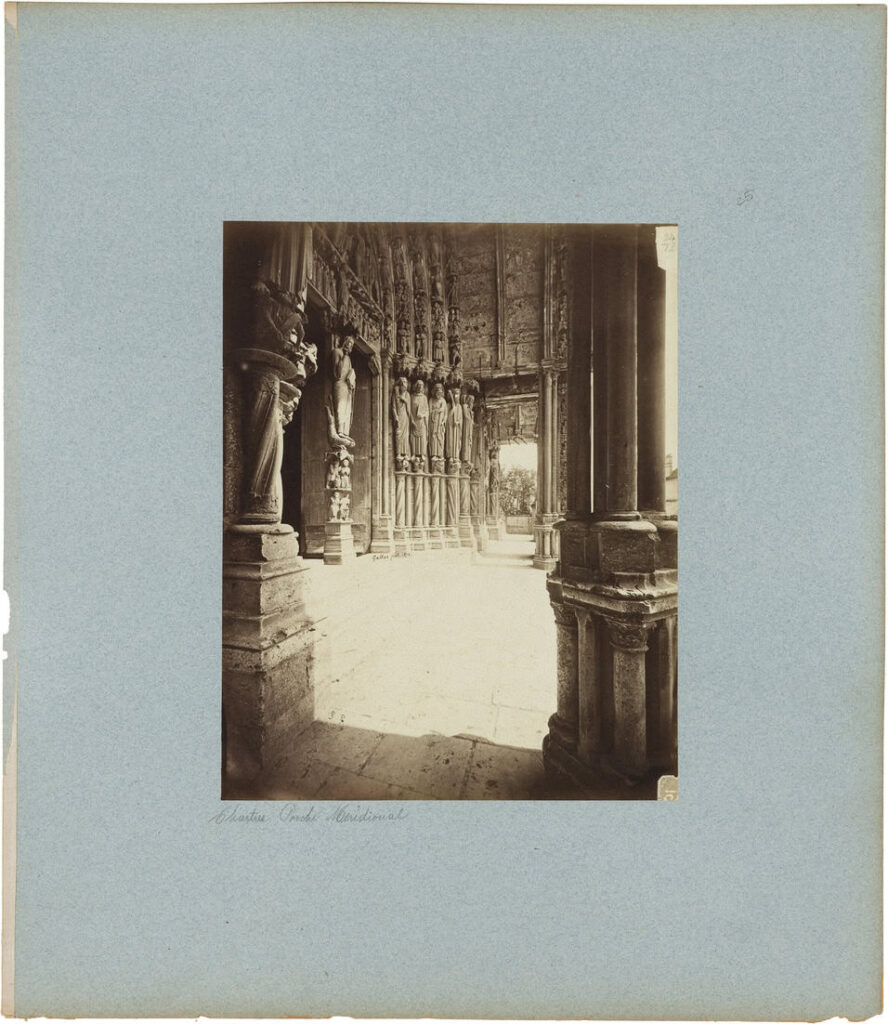

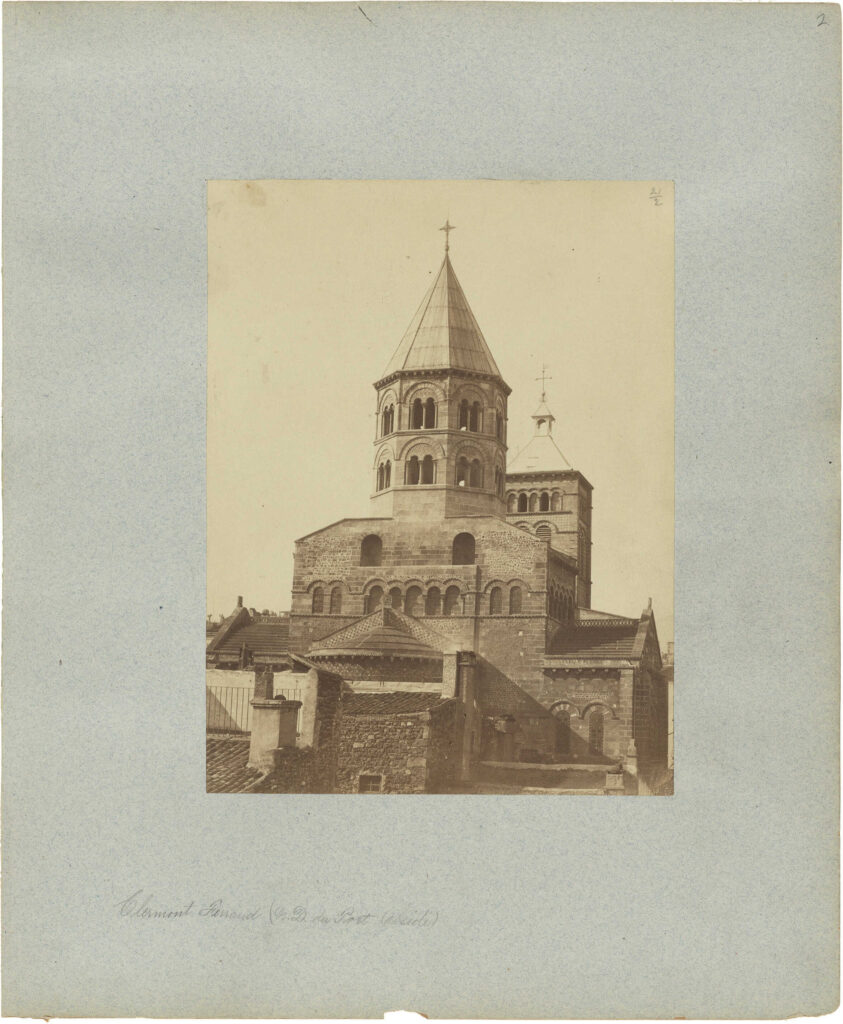

But if Conant’s education acquainted him with multiple historical styles in architecture, including the Romanesque, these styles often served as little more than repositories of isolated morphological options, especially for ornament. Good examples are two Warren drawings for the Alexander Orr house in Troy, NY, one with a Romanesque and the other with a Renaissance entrance porch (figs. 12 and 13), the vocabulary of the latter perhaps drawn from a cast of the balcony from the Palazzo Cancelleria in Rome later displayed in Harvard’s Robinson Hall (fig. 89). This same interest in the evocative part rather than the structural whole is evident in examples from Richardson’s collection of over 3,500 photos now in Special Collections at the Graduate School of Design: a detail of a highly-ornamented Spanish staircase (fig. 14); gothic tracery from Tarragona Cathedral’s south/west portal (fig. 15); the picturesque massing of St. Nectaire rising above vernacular houses in Puy de Dome, France (fig. 16); the fall of light on the trumeau and jamb figures in the south porch at Chartres (fig. 17). Only rarely is architectural structure the main subject of the photograph (fig.18). Of course, these were the photographs available to Richardson for purchase, not images he composed himself, but by circumscribing his understanding of historical architectural form they influenced his own composition. For example, comparing the exterior massing of the church of Nore Dame du Port (Clermont Ferrand) in Richardson’s photo (fig. 18) to the north elevations, interior and exterior, and plan of his 1872 presentation drawings for Trinity Church (figs.19, 20, 21) shows that what he drew from the vaulted crossing flanked by high barrel vaults (the Auvergnat “lantern-transept”) shown in this model was a solution for a well-lit crossing with transepts tall enough to accommodate gallery seating, thereby satisfying his patron’s requirement that every seat afford a good view of the altar and pulpit. This was good and useful knowledge for the architect, but not such as to suggest a deep engagement with Romanesque structural systems. As to style, in comparison to Notre Dame du Port Trinity has much more stained glass, including what is practically a gothic rose window in the transept (fig. 20), and while Trinity’s central tower terminates in a conical roof as at the Auvergnat church, its height and the steep profile of the roof (fig. 22) seem rather more gothic than Romanesque. Looked at closely, the presentation drawings owe a great deal to that love of intricate pattern and textural contrast captured by the historical excerpts of buildings so abundantly represented in his photo collection.

Herbert Langford Warren (1857–1917)

Proposal for the Alexander Orr Residence, Troy, New York (with Romanesque porch) Herbert Langford Warren Collection, E008b. Frances Loeb Library, Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Herbert Langford Warren (1857–1917)

Proposal for the Alexander Orr Residence, Troy, New York (with Renaissance porch) Herbert Langford Warren Collection, Folder E008a. Frances Loeb Library, Harvard University Graduate School of Design

McKim, Mead, and White, architects

Robinson Hall Black-and-white slide, 1904

Frances Loeb Library, Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 77485

Photographer unknown

Church of Saint-Nectaire, Puy-de-Dôme, France Photographs Collected by Henry Hobson Richardson, 1870–1885, HHR218-10. Frances Loeb Library, Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Photographer unknown

Chartres Cathedral, view of South porch, thirteenth century, Chartres, France Photographs Collected by Henry Hobson Richardson, 1870–1885, HHR320-1. Frances Loeb Library, Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Photographer unknown

Notre Dame du Port, view of apse, Clermont-Ferrand, France Photographs Collected by Henry Hobson Richardson, 1870–1885, HHR218-10. Frances Loeb Library, Harvard University Graduate School of Design

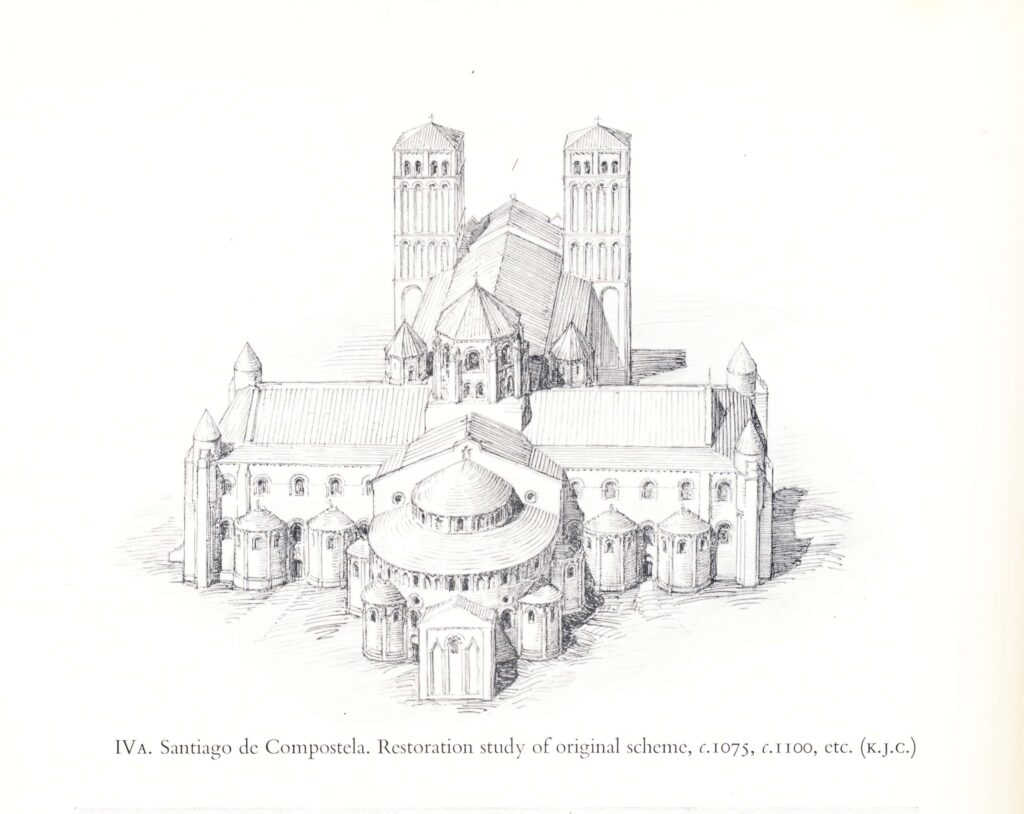

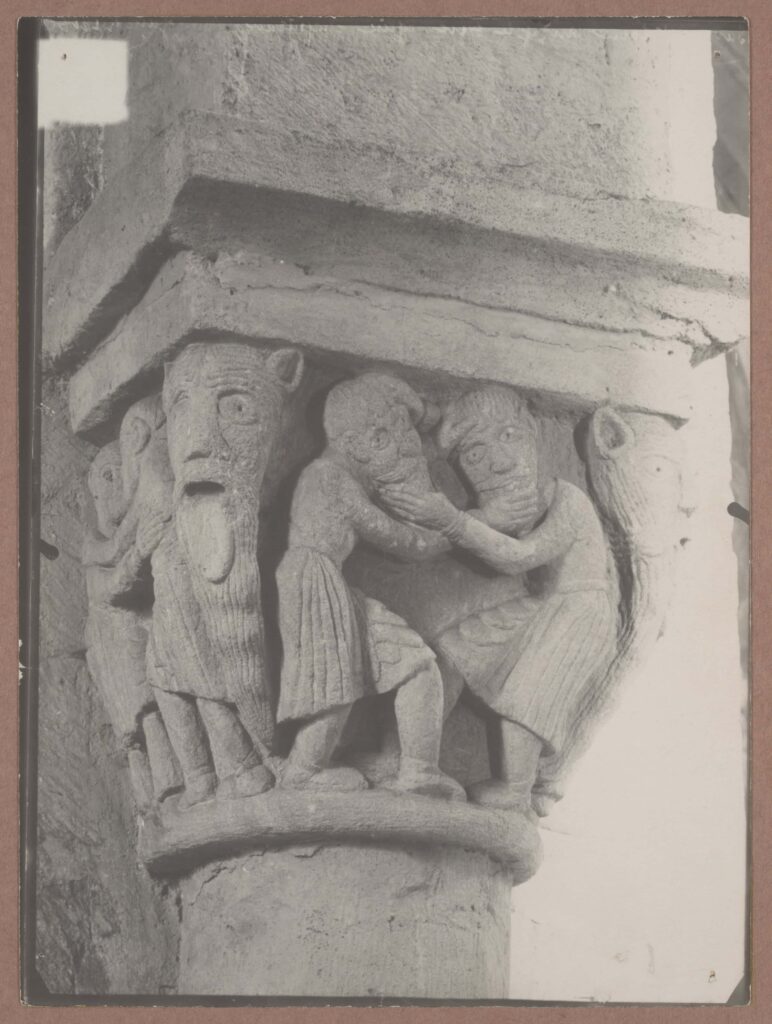

Conant’s understanding of what to do with the past changed when he met Arthur Kingsley Porter (1883-1933) (fig. 23), probably in the same year that Porter left Yale for the Art History department at Harvard, 1921. In the foreward to his Carolingian and Romanesque Architecture, 800-1200 (1959), Conant described himself as “academically the heir of Herbert Langford Warren and his teachers Henry Hobson Richardson and Charles Eliot Norton.”[1] Yet, so Conant continued in the foreward, “the greatest direct indebtedness of the author is to this mentor, colleague, and friend, Arthur Kingsley Porter.” Porter’s reputation as a medievalist had been established in 1909 with his two-volume Medieval Architecture: Its Origins and Development, in which he interpreted buildings within their historical, social, and intellectual contexts; Conant met Porter just before the latter’s ten-volume Romanesque Sculpture of the Pilgrimage Roads (1923) brought the discipline of art history into the twentieth century by presenting a photographic catalogue as a primary research result (figs. 24, 25, 26, 27, 28). Of course, photographs had been used by art historians before this. Charles Eliot Norton (1827-1908), the first professor of Art History at Harvard, may have passed photographs as well as prints round to his students, although his teaching hewed closely to his main interest in the history of the fine arts as connected to literature (the title of his most popular course). Indeed, Conant’s historical scholarship was founded on the photos of ancient, medieval, and Renaissance buildings that Warren, believing that a grasp of the aesthetic principles of great architecture should underlie students’ technical training, had insisted the library acquire. By 1907, at a time when the Fogg Museum owned 3,643 lantern slides, the architecture school already had around 8,000. Richardson, whose own photographic collection contained over 3,500 items, also considered photos to be indispensable resources for architectural knowledge. However, Porter’s systematic visual documentation of sculpture found along medieval routes used by pilgrims regardless of its quality or condition enabled fine-grained scholarly analyses of the diffusion of artistic ideas, methods, and techniques across broad geographic areas, enabling stylistic, cultural, and chronological classifications to be proposed: in short, he employed a scientific method akin to that of biology or other physical sciences. Like Richardson’s photos, Porter’s focused on the telling detail, but these excerpts were either of iconographic interest or to illustrate a particular manner of carving. Importantly, Porter and his wife Lucy (1876-1962) took their own photos: a photo of a statue without its head (fig.28) would have been unthinkable for a commercial photographer to sell. But if, for Porter, the point was to document the linear, wavy, and zig-zag patterns of the figure’s drapery, its head was irrelevant. In another example, this one from Ste. Foi at Conques around 1120 (fig. 27), Porter captured a secondary figure,the hung man, rather than the devil himself as the photograph’s center of interest. Porter here sacrificed symmetrical composition for the significant detail because since this same, or a very similar, hung figure appeared on a capital at St. Lazare, Autun, in Burgundy within the same decade, connections between the two chantiers might be hypothesized. Later, Conant would adapt Porter’s method of classification by type to architecture, distinguishing a group of important Romanesque churches with similarities in plan and elevation as the “pilgrimage group,” one on each of the main roads from France to Santiago de Compostela: St. Martin at Tours, St. Martial at Limoges, Ste. Foi at Conques, and St. Sernin at Toulouse (fig. 31).

Photographer unknown

Arthur Kingsley Porter (1883–1933) and Lucy Porter (1876–1962) in their car

Harvard University Archives, HUG 1706.125 Box 1

Arles, Bouches-du-Rhône, St.-Trophime, Western Facade, Northern End, twelfth century.

Print reproduction of photograph 175 Ar53 2TW 2j. Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University

Lucy Wallace Porter (1876–1962)

Anzy-le-Duc, (Saòne-et-Loire), Capital of Nave, Notre-Dame-de-l’Assomption

Print reproduction of photograph 175 An99 2(A)1e 3a3. Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University

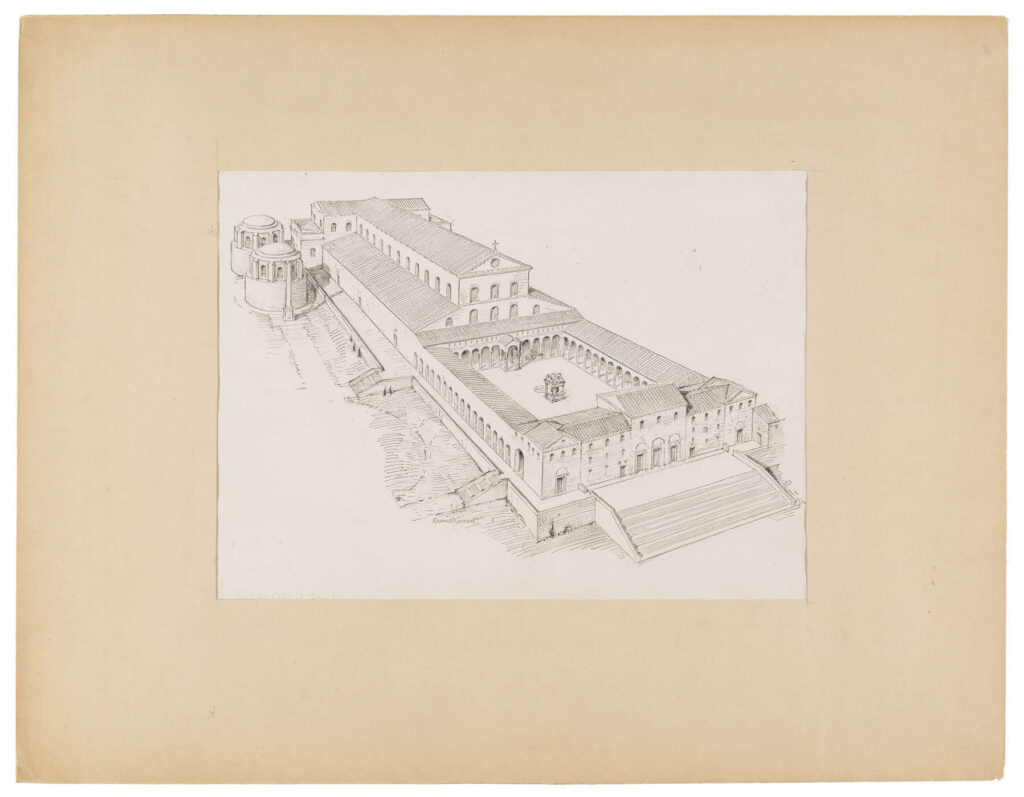

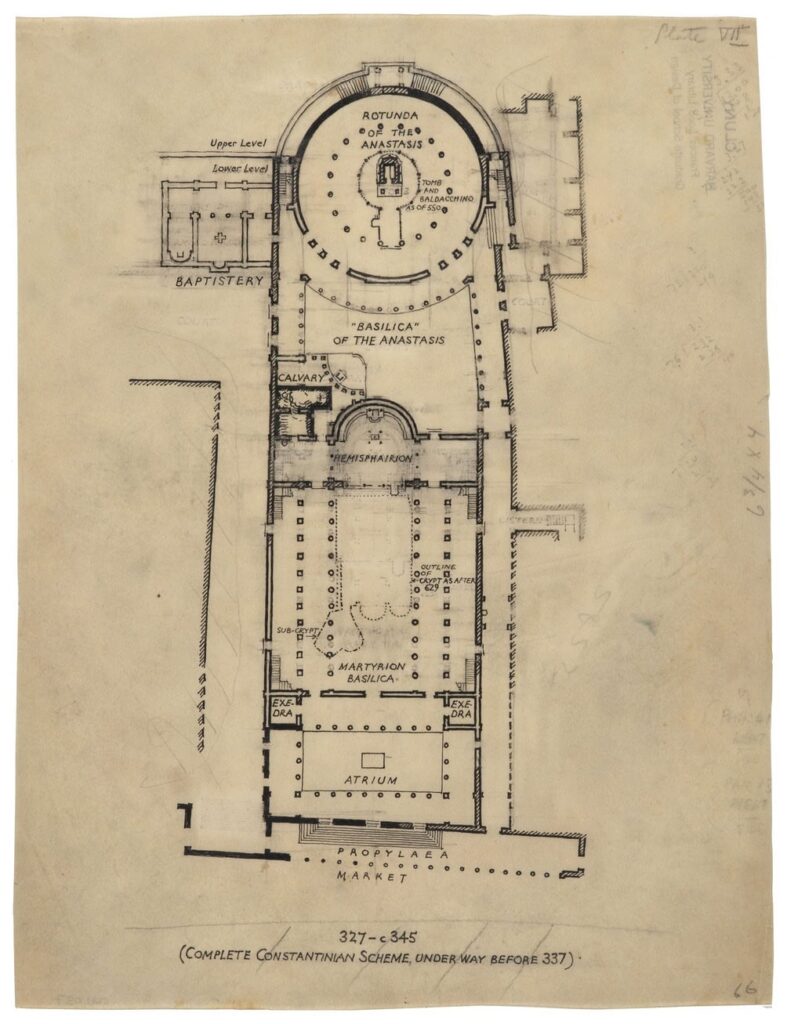

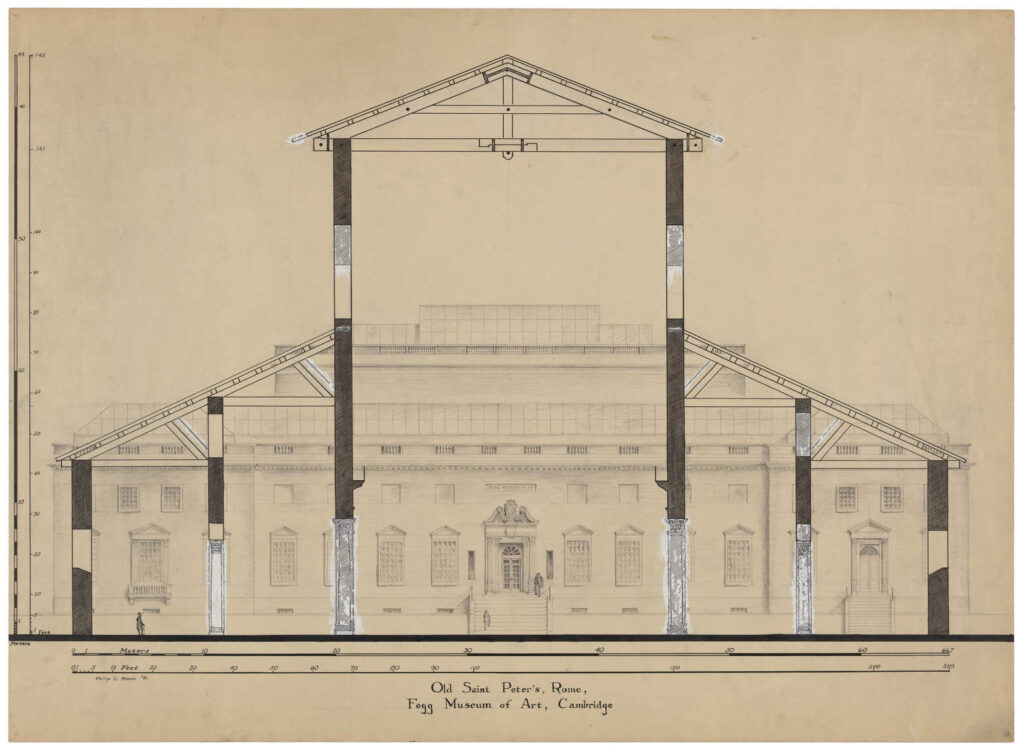

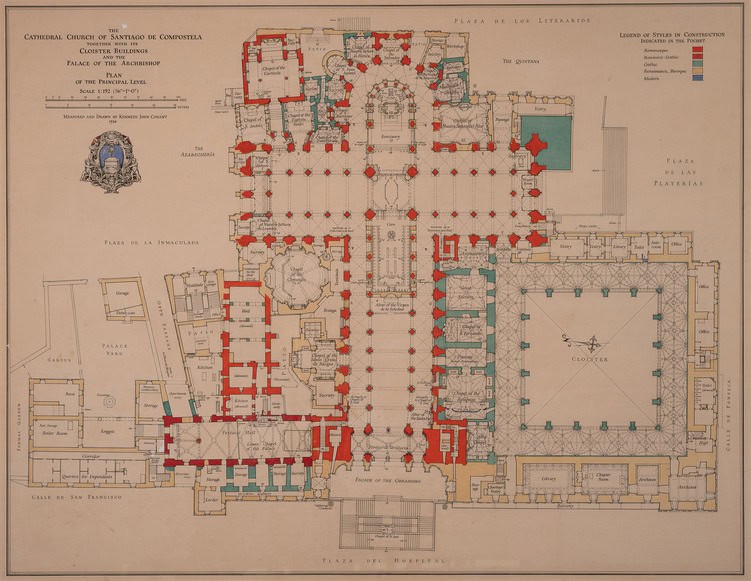

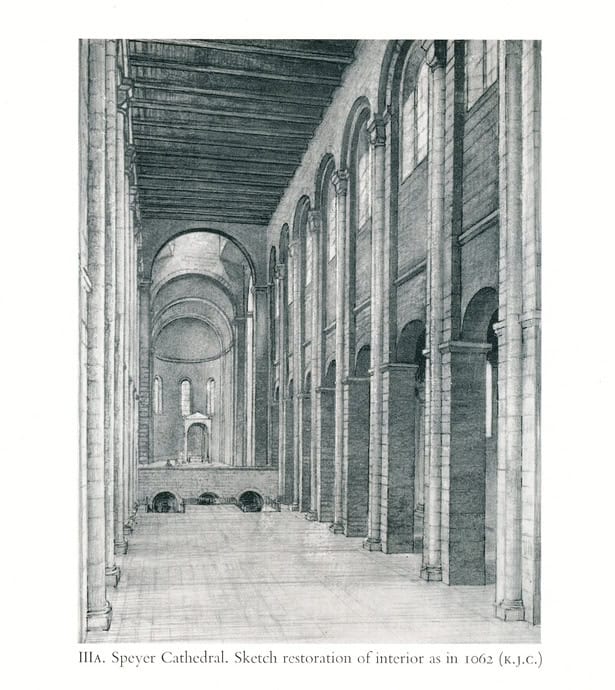

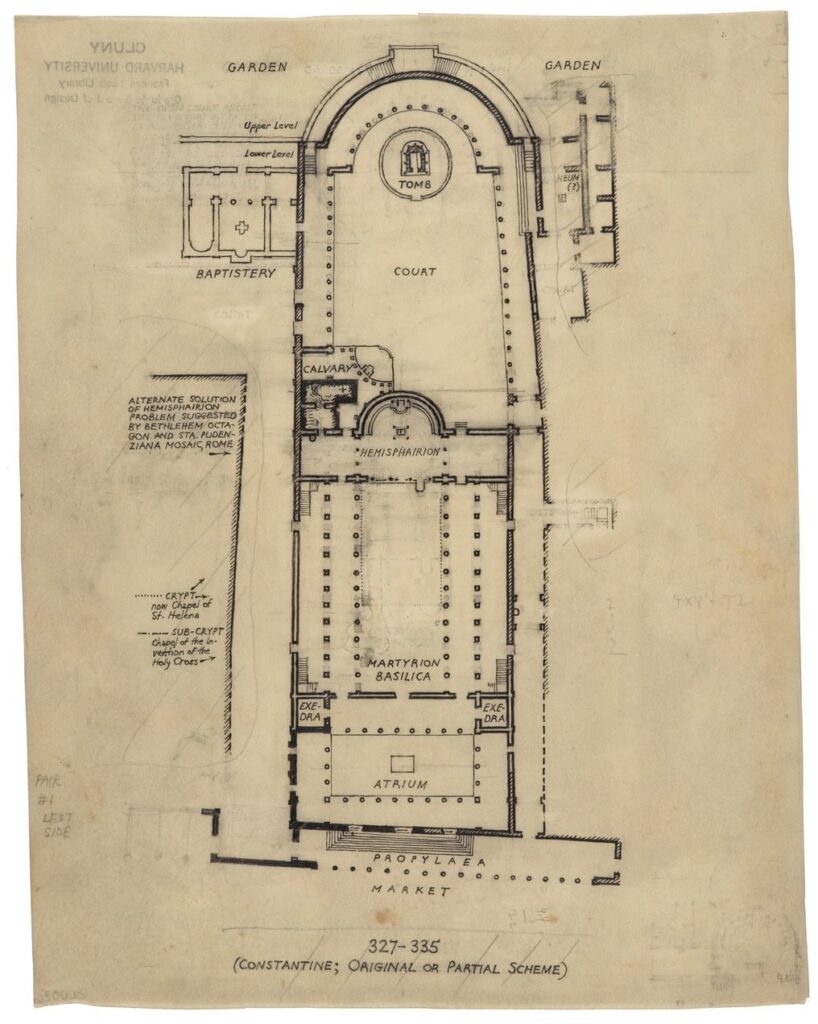

Under Porter’s direction, Conant wrote his Ph.D. dissertation titled The Early Architectural History of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela (1925). Compostela was the end goal of the pilgrimage routes studied by Porter and, later, by Conant. While Conant meticulously documented the (then) current state of the building fabric (fig. 29), his purpose was to discover the original design for this extraordinarily consequential church. As his dissertation title acknowledges, buildings have histories – they evolve and change over time. Today, many scholars of medieval building believe this to be true even within the original building process itself, theorizing that buildings were continuously re-designed in successive, annual building campaigns, since construction took place only when weather permitted, essentially from spring to fall. The idea that there was an original design for the entire building before construction started and that the built building was essentially the realization of this holistic conception is considered unlikely by many scholars today.[2] But for Conant, the very aim and purpose of establishing a building’s chronology was to reveal its original state and, by removing later alterations, to make manifest the original idea of its architect. He proposed such solutions for Santiago de Compostela (figs. 30, 32) and other medieval and Renaissance buildings such as the monastery of Montecassino, Saint Denis outside Paris, Speyer cathedral, St. Sophia in Kiev, and St. Peter’s in Rome (figs. 33, 34, 35). In one unusual case, The Holy Sepulcher complex in Jerusalem, he proposed an early original phase as begun by the emperor Constantine 327-335 A.D. and a later original state as completed eight years after Constantine’s death in 337 (figs. 36, 37). Since the physical fabric of the extant complex didn’t permit such fine distinctions, this shows how closely Conant relied on literary sources and their interpretation in the scholarly literature for his reconstruction drawings. Yet Conant thought like an architect. We see this in his choice – novel, as far as I know—to represent Hagia Sophia from the apse rather than facade because that view best reveals how half domes, barrel vaults, and buttresses supported the buiilding’s first, failed, dome (fig. 38). His architectural imagination, while always based on sober facts, was sometimes witty, as when he contrasted a transverse section of the simple monumentality of Old St. Peter’s immense structure to the rather fussily worked surfaces of the new Fogg Museum as if commenting, “this is a façade, that is a space.” (fig. 39). Conant had an extraordinary ability to envision what no longer physically existed. And he restored to our minds and eyes the original appearance of the Abbey of Cluny III.

Kenneth Conant

Santiago de Compostela complex. Plan of the basilica and adjacent structures with later changes and additions

Kenneth Conant Speyer Cathedral. Sketch Restoration of interior as in 1062, from Kenneth Conant, Carolingian and Romanesque Architecture, 800–1200, Baltimore, 1959

Kenneth Conant

Reconstruction sketch of the Holy Sepulcher complex in Jerusalem as in 327–335

The Cluny Collection

Exhibition: Envisioning Cluny: Kenneth Conant and Representations of Medieval Architecture, 1872–2025

Curator: Christine Smith, Robert C. and Marion K. Weinberg Professor of Architectural History

Collaborators: Matthew Cook, Digital Scholarship Programs Manager, Widener Library; Ines Zalduendo, Special Collections Curator at the Frances Loeb Library, M.Arch ’95

Animation: Clayton Scoble, Media Lab Director, Lamont Library

Assistants: Kian Hosseinnia, M.Arch ’24; Hayley Eaves, Ph.D Candidate

Exhibition Design: Dan Borelli, Director of Exhibitions, GSD, M.Des ’12

Online Exhibition Design: Ashleigh Brady, Archival Collections Website Editor, M.Arch ’26