“Ah, Cluny…How Wonderful…Only Paradise is More Beautiful”

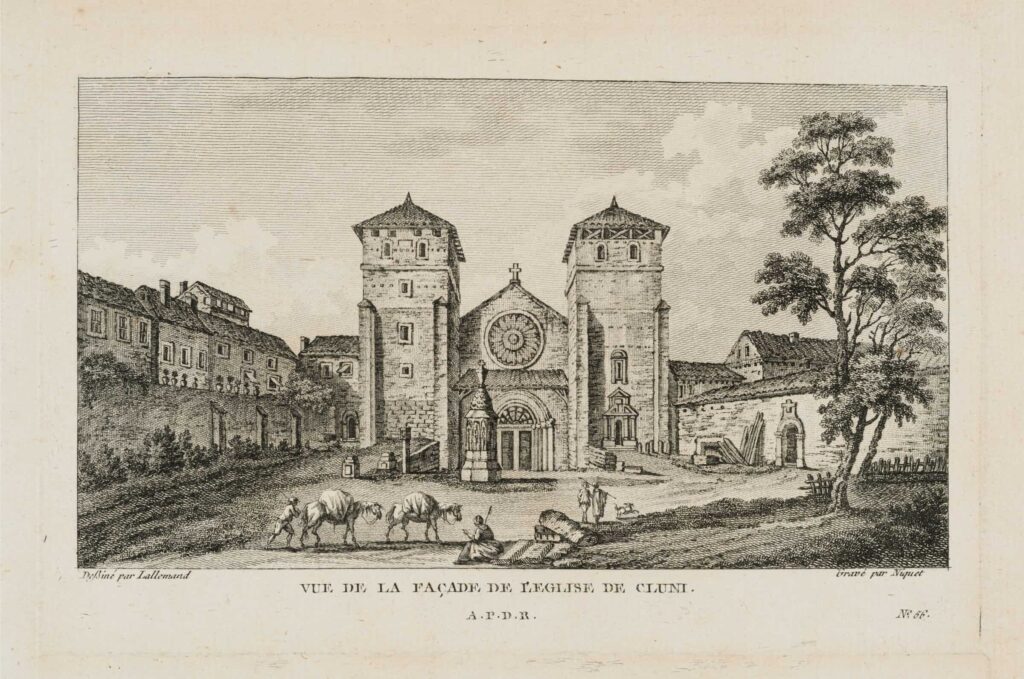

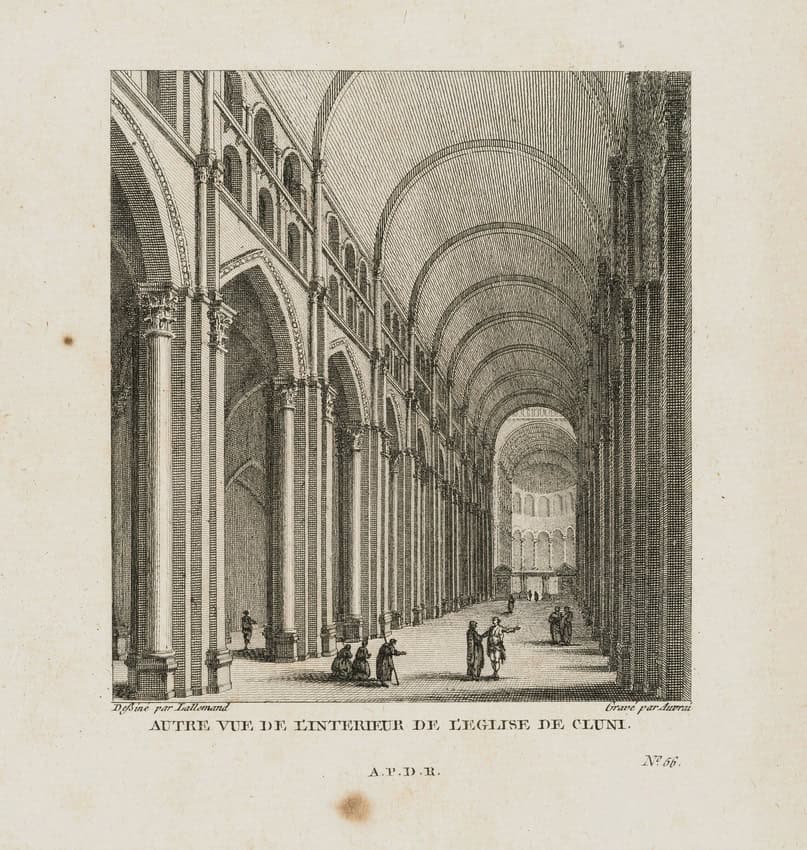

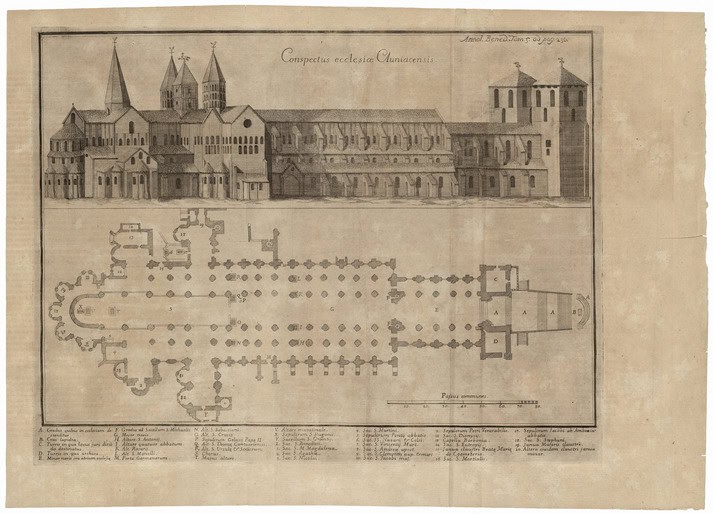

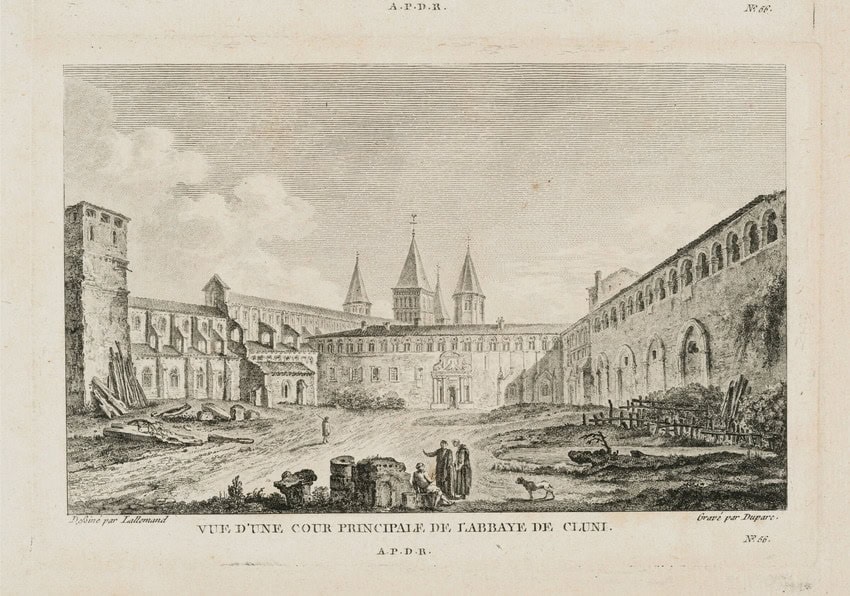

The reformed Benedictine abbey of Cluny in central France, founded in 910, was so attractive to those seeking monastic profession and grew in numbers so rapidly that no less than three church buildings were erected on the property on the same or adjacent sites within 200 years: scholars refer to these as Cluny I, II, and III. The last and greatest of these, begun in 1088, stood until the French Revolution and was dismantled – some of it even dynamited – between 1792 and 1819. Of the physical fabric, only the major and minor south transepts and parts of the south ambulatory aisle remain above ground (fig. 40). The whole monastic complex is known from prints, seven of which were given by Conant to Harvard’s Fogg Museum (41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47), as well as from drawings, documents, and literary accounts. From these sources we know that Cluny III was, at completion around 1130, the largest building north of the Alps, measuring some 500 feet long and 100 feet high. It was unusual not only in size but in form, having two transepts and a total of eight towers and was among the earliest buildings north of the Alps to have an ambulatory with radiating chapels, pointed arches, and flying buttresses in the nave. We see it still intact in P.-F. Giffart’s 1713 plan and elevation for Jean Mabillon’s Annales ordinis S. Benedicti occidentalium monachorum patriarchae (fig. 48).

Frédéric [Palmier ?], photographer

Cluny III, Southwest Transept (the only part of the building still intact)

Kenneth Conant

Cluny III showing existing masonry in relation to present structures: the stallion depot, a charter school, a hotel, and houses

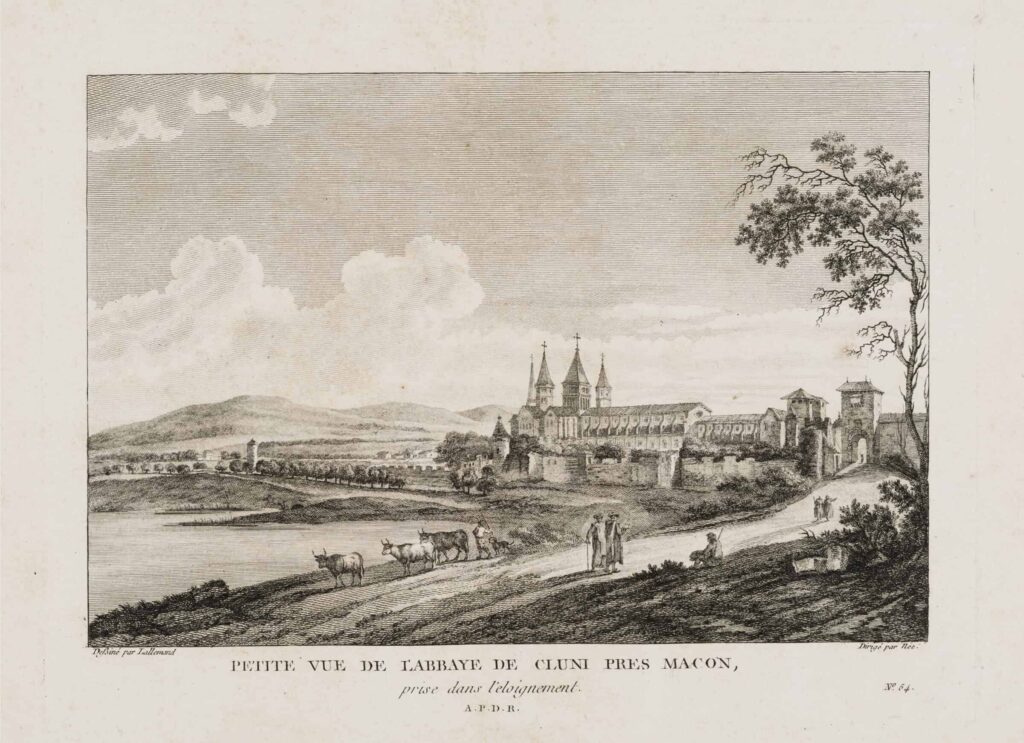

Unidentified artist under the direction of Louis Joseph Masquelier, after Jean-Baptiste Lallemand (1716–ca. 1803)

View of the Town of Cluny near the Levée bridge Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College, M14956

Marie Alexandre Duparc, (active ca. 1780–1820), after Jean-Baptiste Lallemand (1716–ca. 1803)

View of the Main Courtyard of the Abbey of Cluny, 1787

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College, M14955

Pierre Laurent Auvray (b. 1736), after Jean-Baptiste Lallemand (1716–ca. 1803)

Interior of Abbey of Cluny from the Side of the Entrance

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College, M14952

François Denis Née (1732–1817), after Jean-Baptiste Lallemand, (1716–ca. 1803)

View of the Abbey of Cluny, 1781

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College, M14955

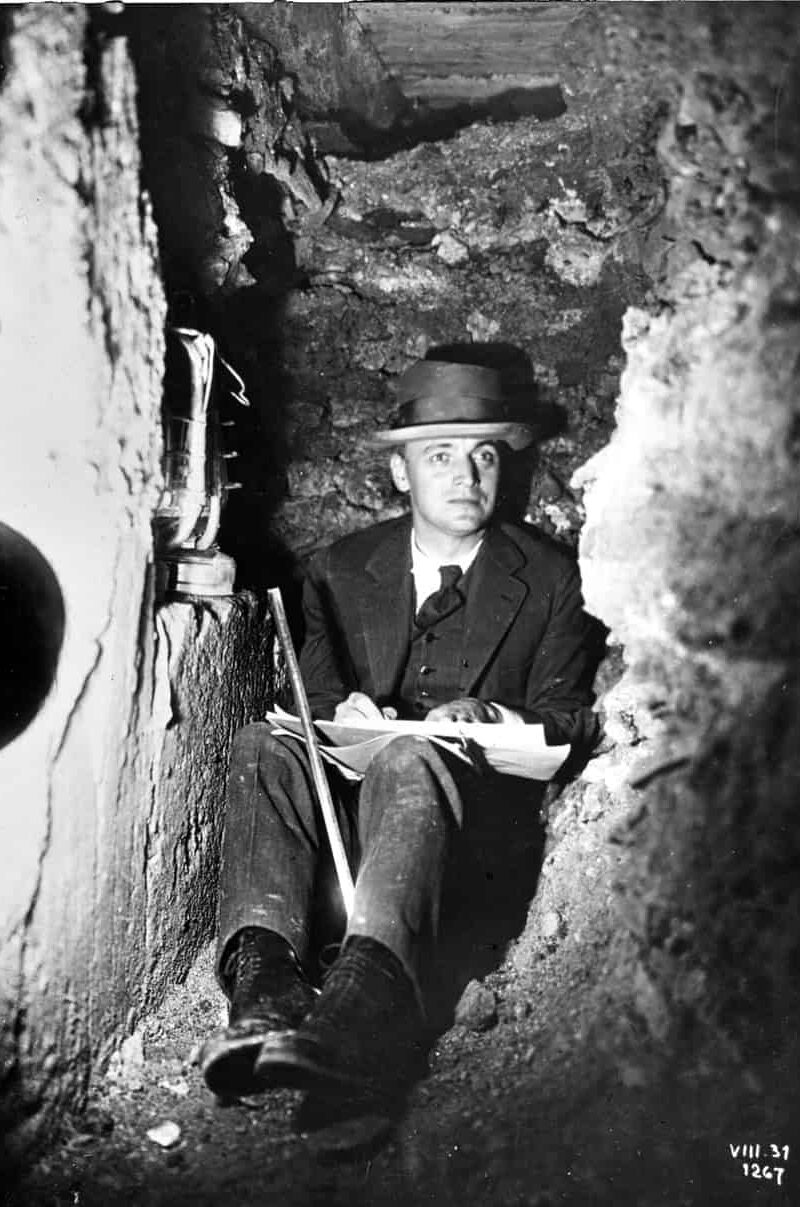

For Conant, who began studying its ruins in 1925, Cluny III was “certainly the premier church of the Romanesque style” and “the center of western monasticism in the Romanesque period”[3]– the non plus ultra both aesthetically and culturally, a kind of eighth World Wonder. He longed to see it and to know it as it had once been. To this end, he learned how to plan an excavation using pits at archeological digs at Chichen-Itza and Pueblo Bonito and in 1928, having received funding from the Medieval Academy of America and the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, he began excavations at Cluny that would continue until 1950 (fig. 49). Having contributed regular updates on his discoveries to Speculum (published by the Medieval Academy of America) he concluded the project with his magisterial publication Cluny: Les églises et la maison du chef d’ordre (1968). When Gund Hall opened in 1972 he donated his research materials to the Francis Loeb Library’s Special Collections at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. Most of the materials in this exhibition come from the Cluny Collection.

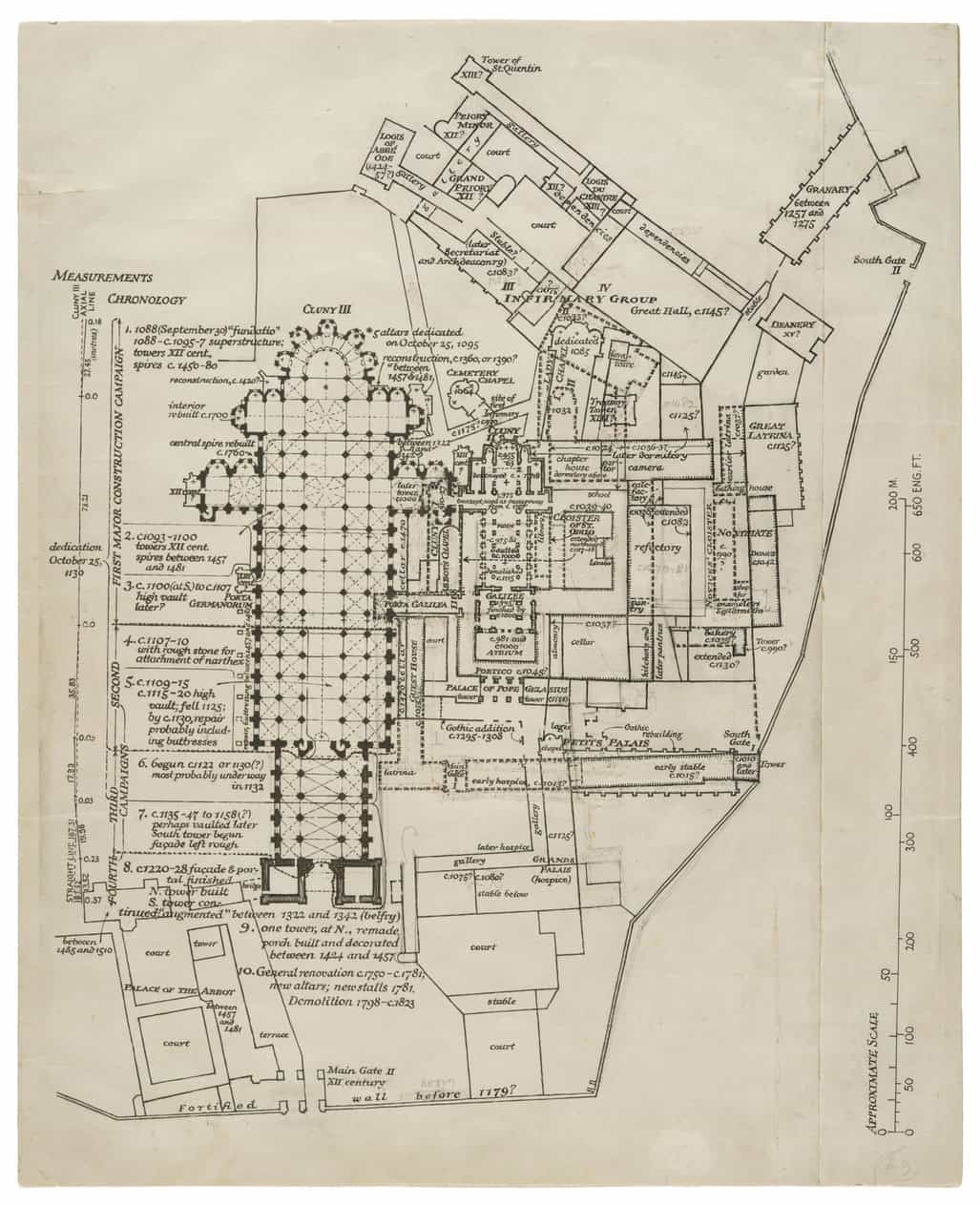

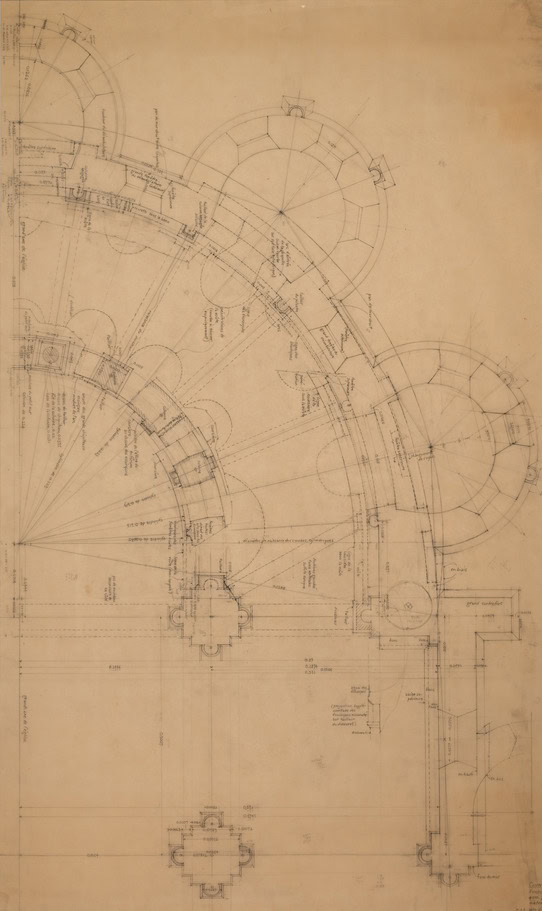

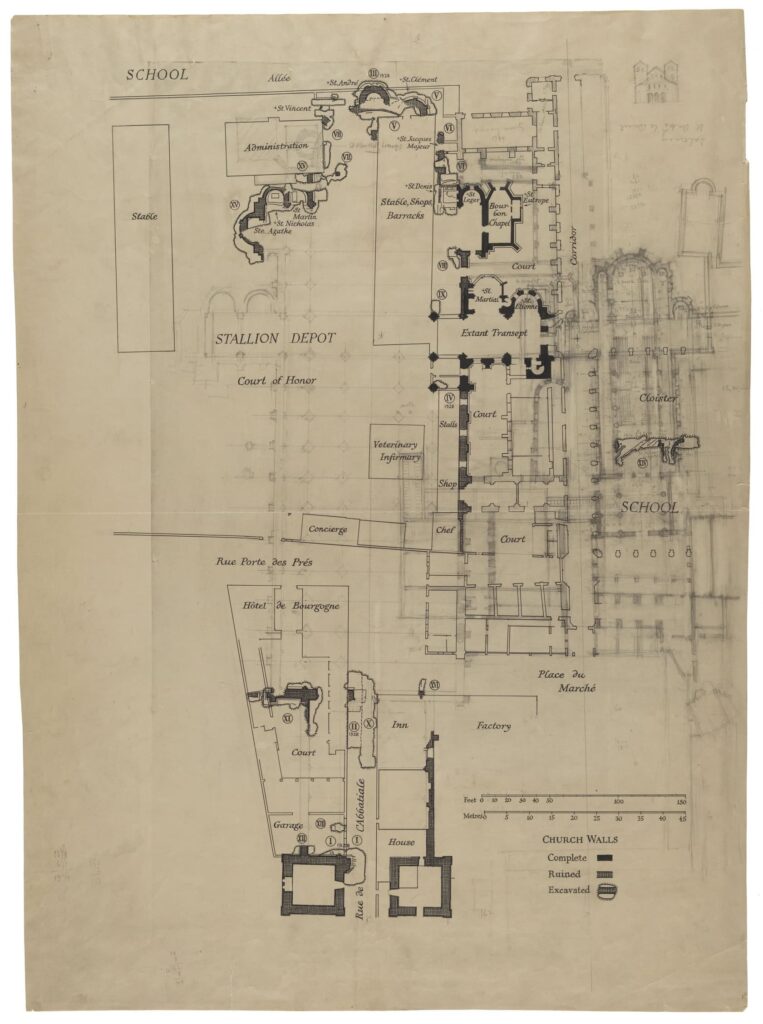

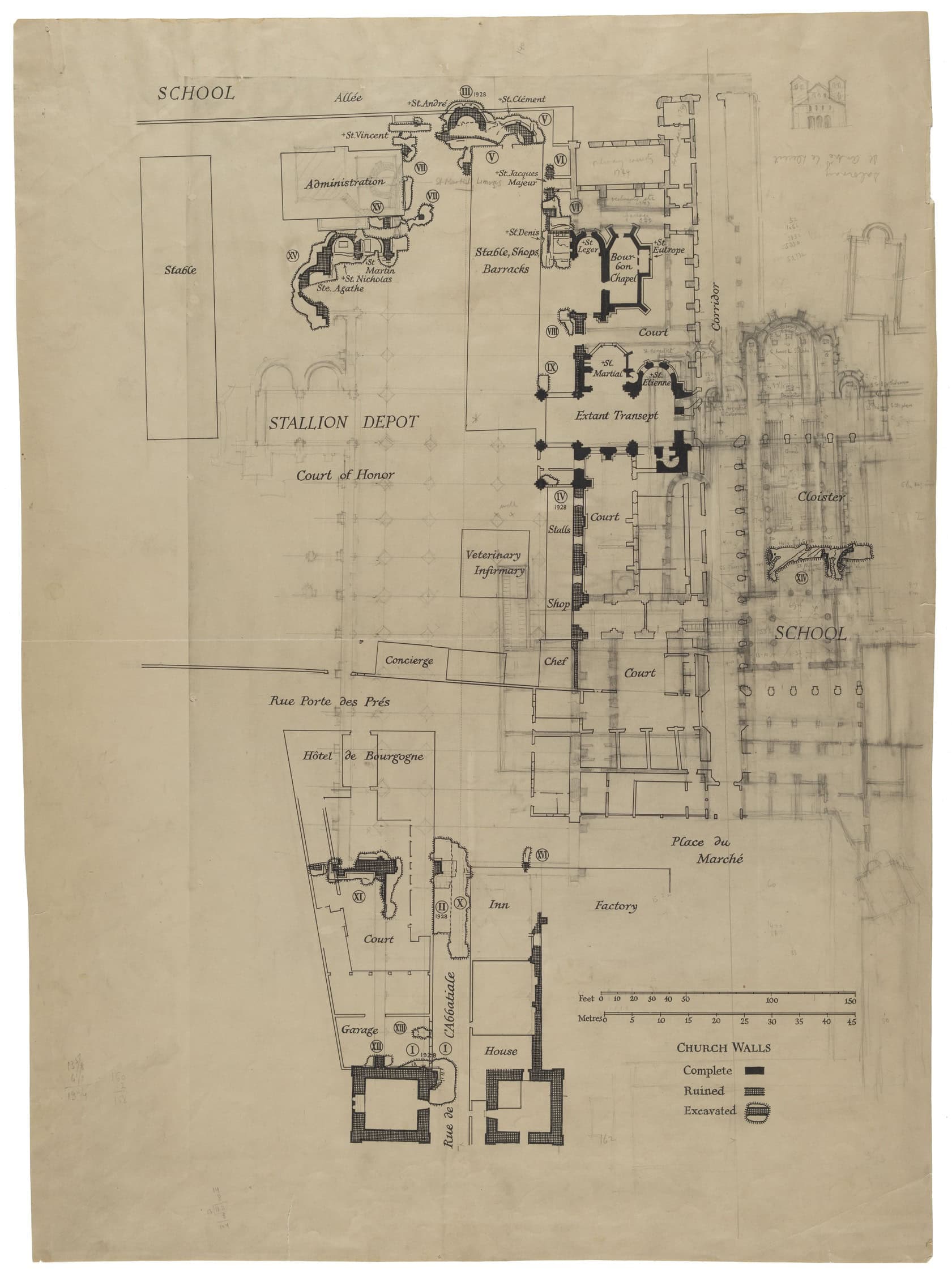

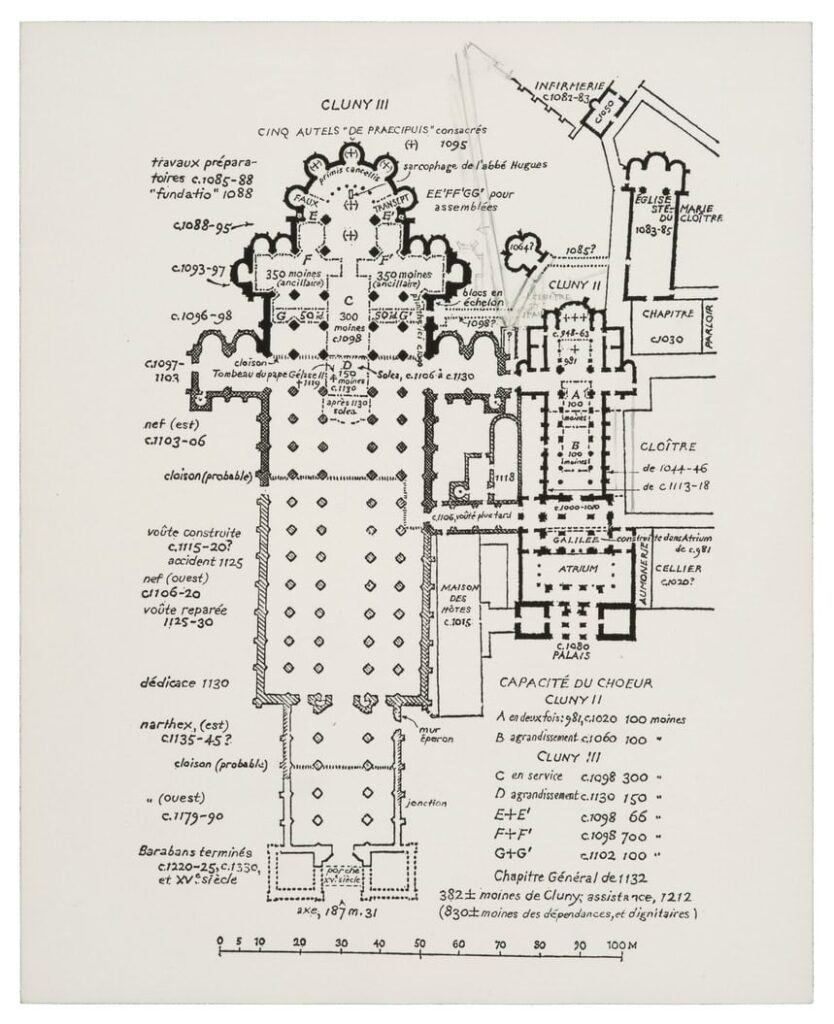

Conant began by documenting the present state of Cluny’s site: there were some architectural remains, a stallion depot, school, hotel and houses (fig. 50). By “began” I mean intellectually, not chronologically. Since Conant worked and re-worked plans, diagrams and views of Cluny over four decades, I could only speculate on the dates of specific studies. Figures 51 and 52, for instance, have essentially the same plan of the churches Cluny II and III but Conant used this same graphic to visualize different historical questions. The notations on figure 51 calculate how many monks could fit into the new spaces of Cluny III, assuming 8.6 square feet per monk plus his faldstool. By relating the addition of space to the growth in numbers of the community, Conant argued that whereas Cluny II could hold no more than 200 monks, phase 1 of Cluny III could fit the 300 monks, which we know from literary sources was the actual number of the community around 1100. So, Conant maintained, the reason for abandoning Cluny II for Cluny III was the need for more monastic choir space. Conant used similar reasoning as proof that construction of Cluny III began at the east end with the choir and chevet where the 300 monks could be accommodated within the newly available 2,000 square feet of space and not at the western transepts as others had argued.[4] Whether his reasoning sufficiently accounted for factors such as the different places assigned to choir versus lay monks, and the difficulty of choir monks to see each other and the cantor across the eastern transept may be questioned, but that is not our point. By contrast to figure 51, although figure 52 also tracks construction from east to west, the notations are concerned with measurements, with structural accomplishment and failure, and with structural repairs. Conant used essentially the same plan to think through different historical problems. The very process of visualization was, for him, the means of thinking historically. For this reason, he used diagrams over and over for different purposes. Not only would it be difficult and perhaps impossible to date these templates, it might not increase our knowledge of Conant’s thinking.

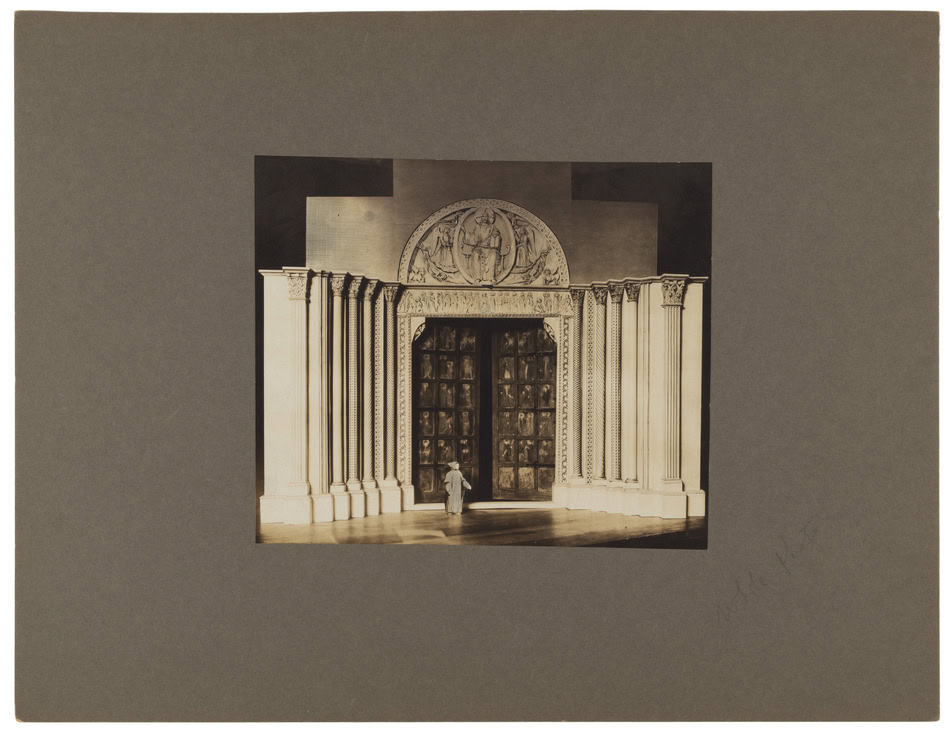

Conant’s visual imagination integrated the present reality of Cluny with what had once existed in a variety of ways using various media. For example, using an aerial photo of the town of Cluny, Conant collaged on to it a photo of a model of Cluny III in the Cluny museum (Musée Ochier) and added around it in pencil the original monastic complex with walls and service buildings (fig. 53). Having realized that the lowest parts of the two thirteenth-century towers of the west façade still existed incorporated into houses, Conant envisioned the interior elevation and vaults of Cluny III above and behind these, extending deep in recession (fig. 54). Around a photograph of an extant capital from Cluny’s apse, Conant re-created its original architectural context in pencil: the half-column and its necking engaged to the coursed limestone masonry; a string course or echinus and abacus supporting an arch with its classicizing molding (fig. 55). The degree and kind of classicism of Cluny III would remain another topic of disagreement among scholars.[5] One of his most extraordinary re- creations is a photo of a model of the original west portal collaged with other elements both drawn and photographed; a “monk” stands in the doorway to provide scale (fig. 56).

Unknown photographer

Kenneth Conant in an excavation trench at Cluny

Photograph. Modern print from a lantern slide

Frances Loeb Library, Harvard University Graduate School of Design, B 398/x19

Kenneth Conant

Cluny III showing existing masonry in relation to present structures: the stallion depot, a charter school, a hotel, and houses

Kenneth Conant

Reconstruction of Cluny II (right) and Cluny III (left) with notations on the chronology of construction, identifications of places, and liturgical furnishings

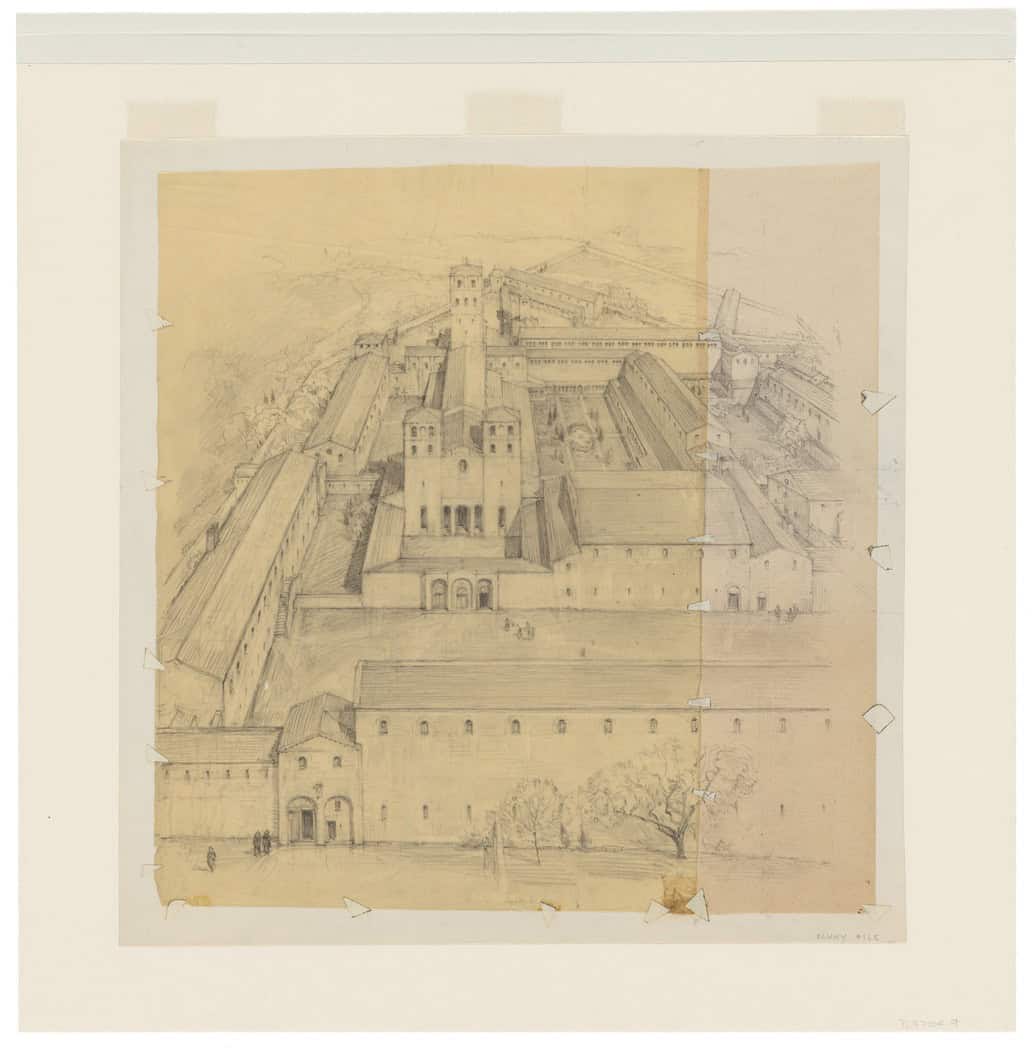

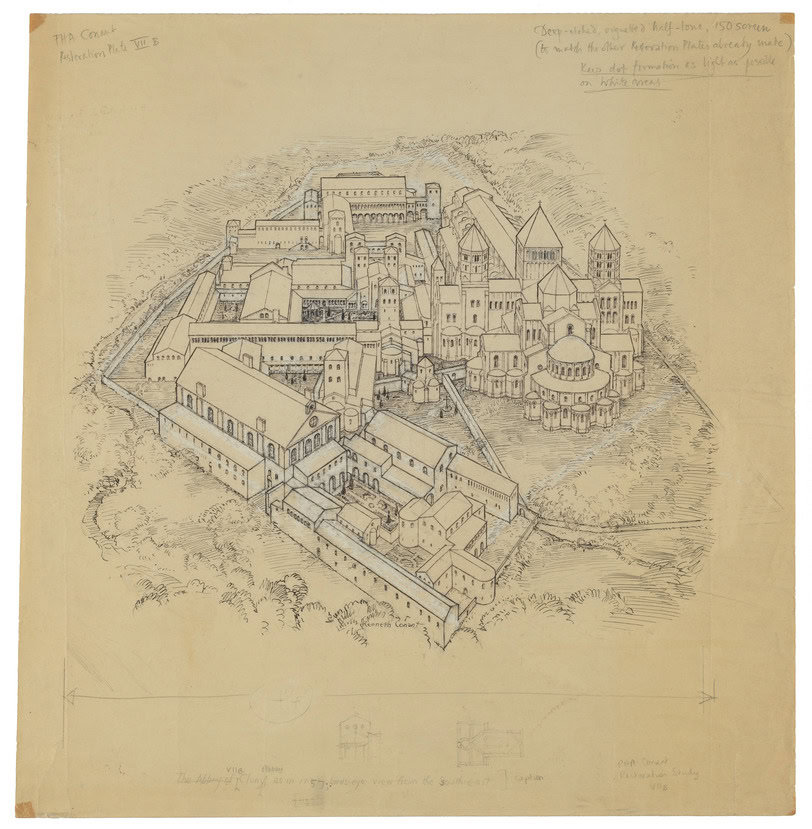

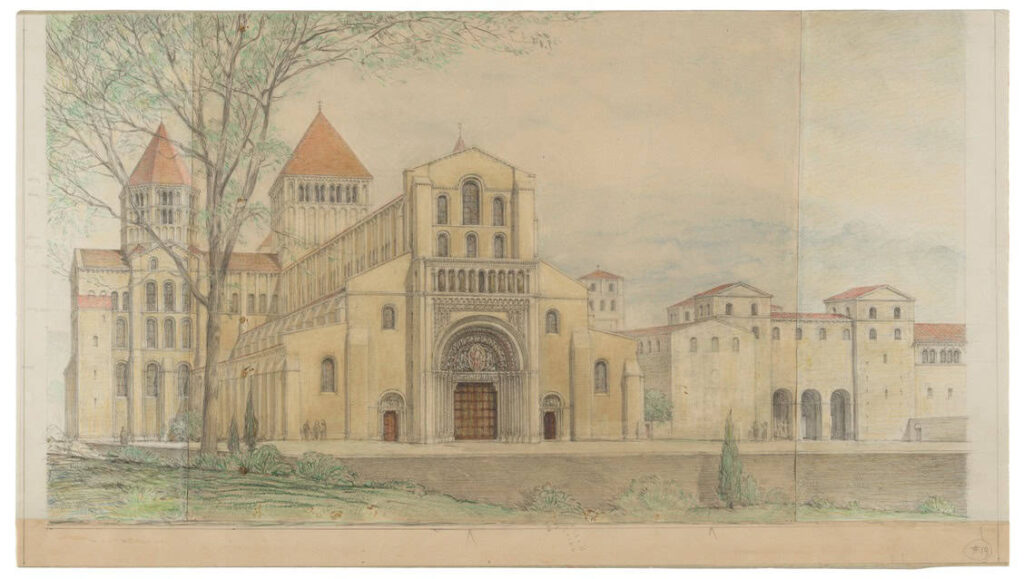

As with Santiago de Compostela, Conant established a chronology of construction for the abbey church and monastic structures. One way to represent evoluton over time was to illustrate the entire complex at different key moments. We show a bird’s eye view of Cluny II as it might have appeared around 1050 and one of Cluny III around 1157, the latter a view from the apse and before the addition of the western narthex or galilee and its twin-towered façade (figs. 57, 58). Such holistic reconstructions were and are among the most controversial of his historical contributions both because this kind of historical representation inevitably includes inventions by the author without sufficient (or any) evidence and because the evidence at Cluny is itself so scanty as to permit diverse interpretations of what evidence there is. Scholars today who make digital reconstructions of historical buildings are challenged by this same problem since every smallest detail is represented in a digital model with the same certainty whether it is documented, hypothesized, or invented. Figure 59, a view of Cluny in 1157 looking at the west façade, further reveals how once Conant worked out his understanding of the monastic buildings and their relations to each other, he added landscape, small figures around the buildings, and sky in colored pencil creating a pictorial scene. We see the monastery over a high wall from outside; a tall tree in the foregound cut off by the frame lends some informality to the view, like a snapshot. But Conant the historian distances the reality envisioned by Conant the architect by the image’s abstract pale coloring and a uniformly matte texture.

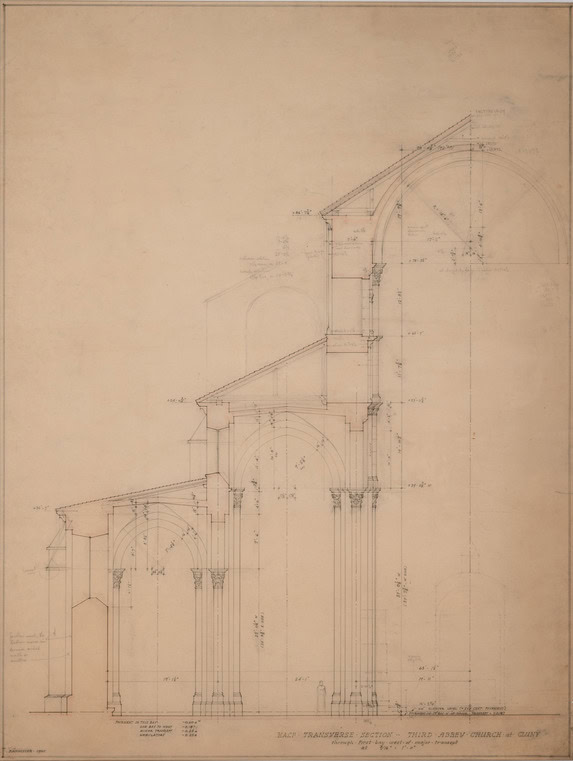

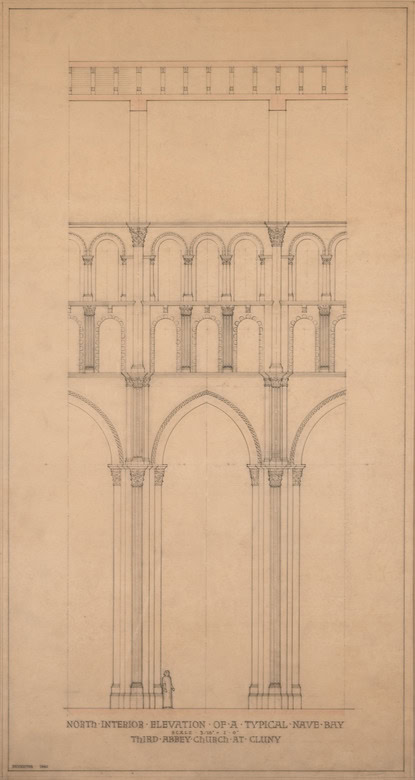

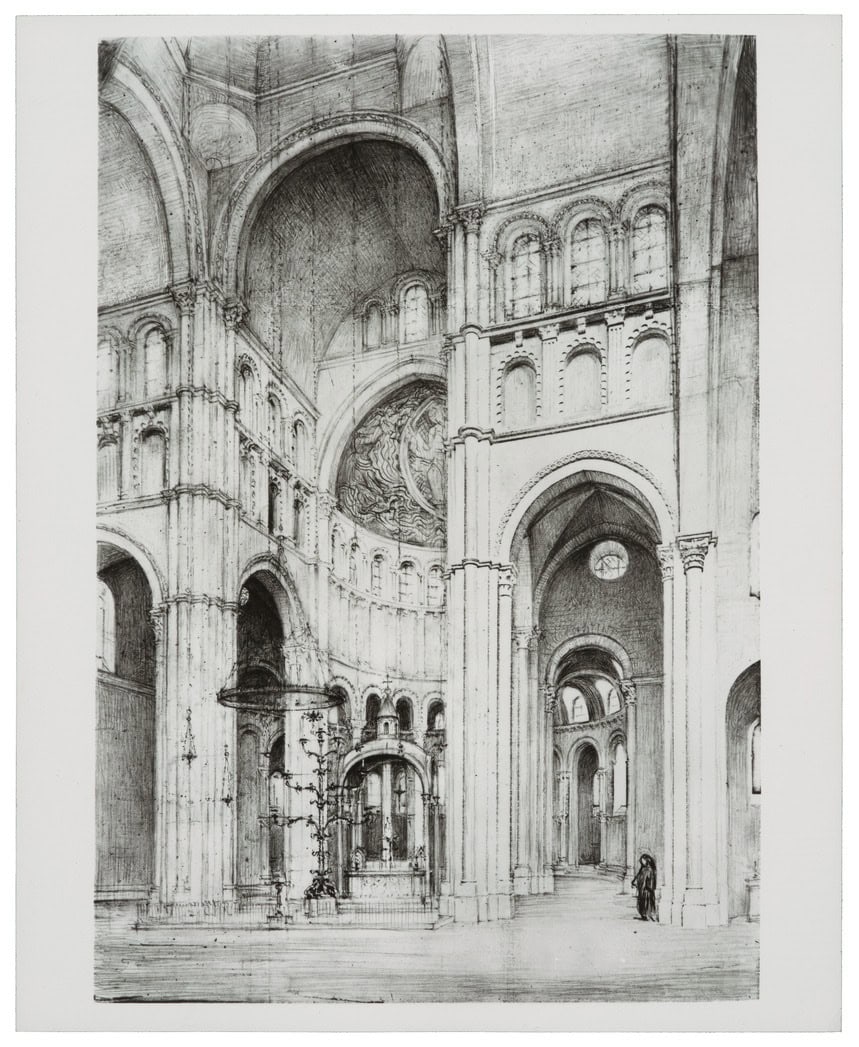

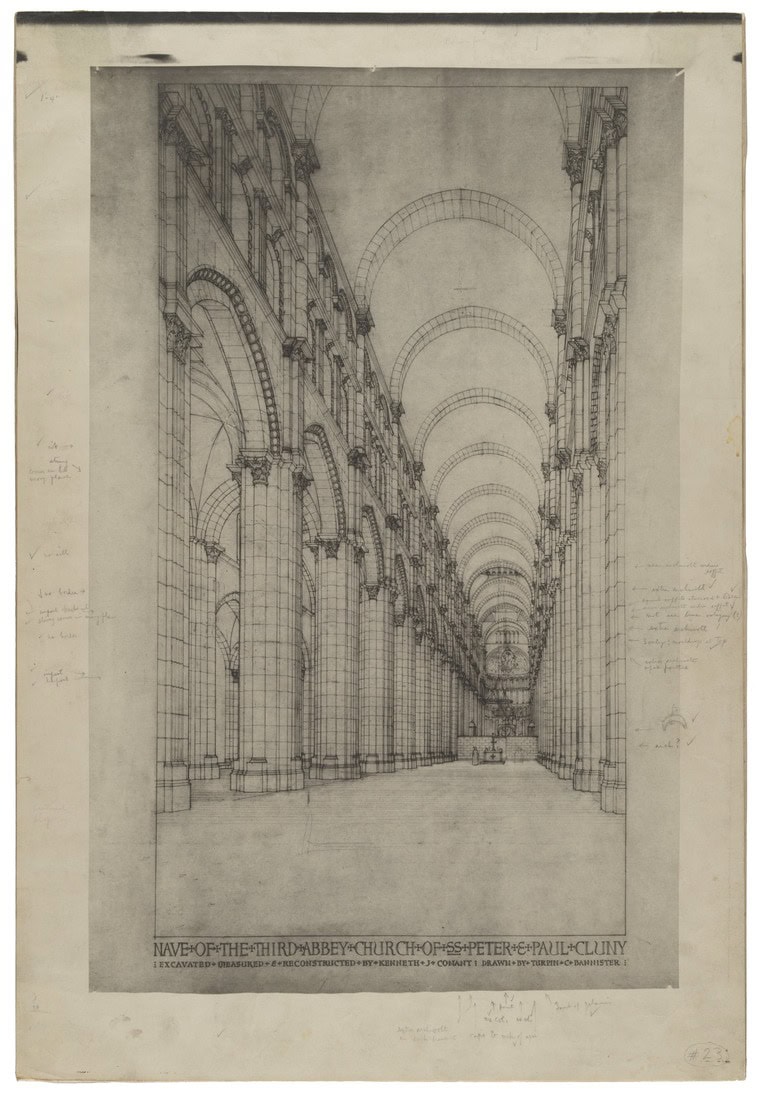

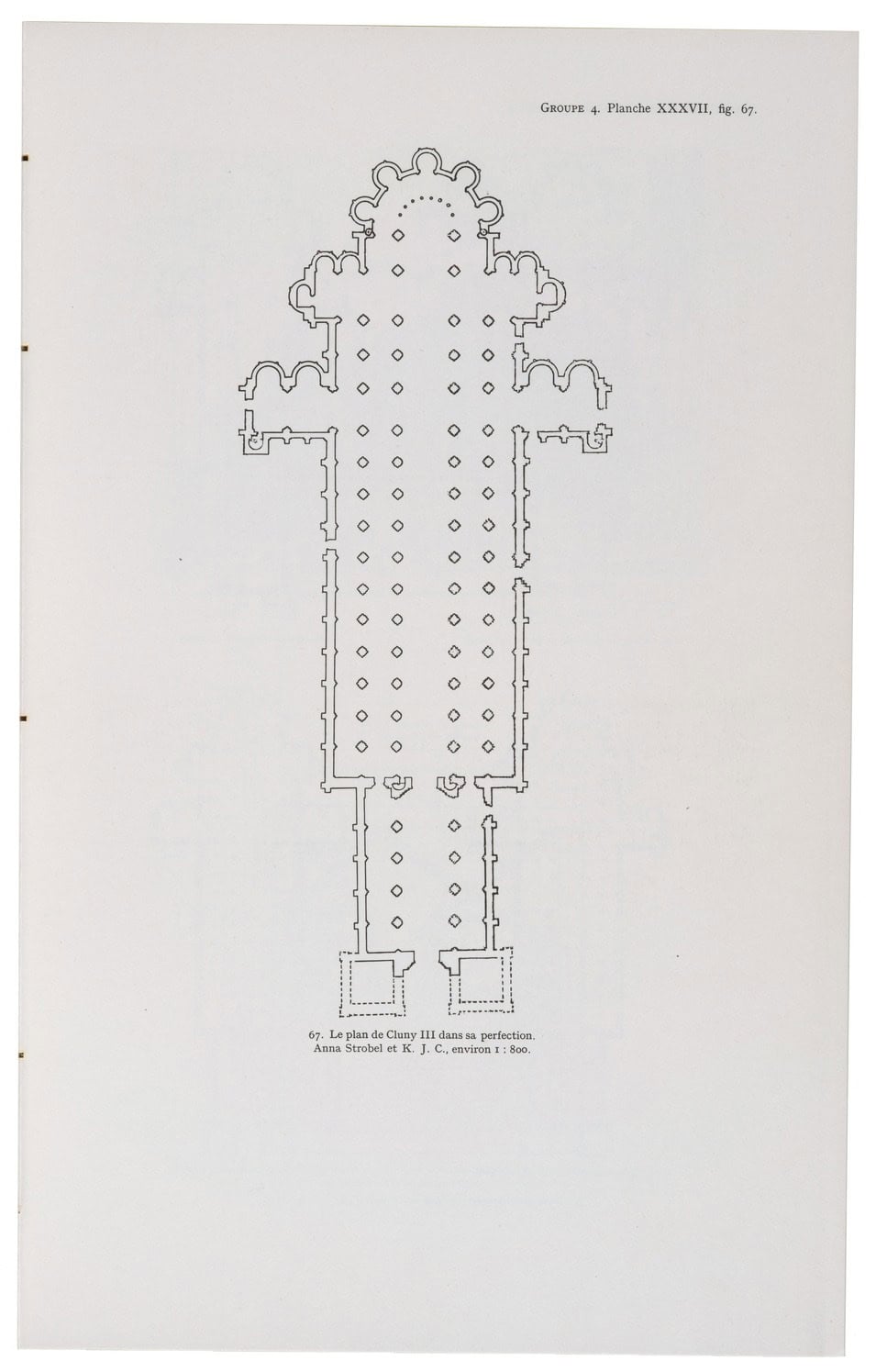

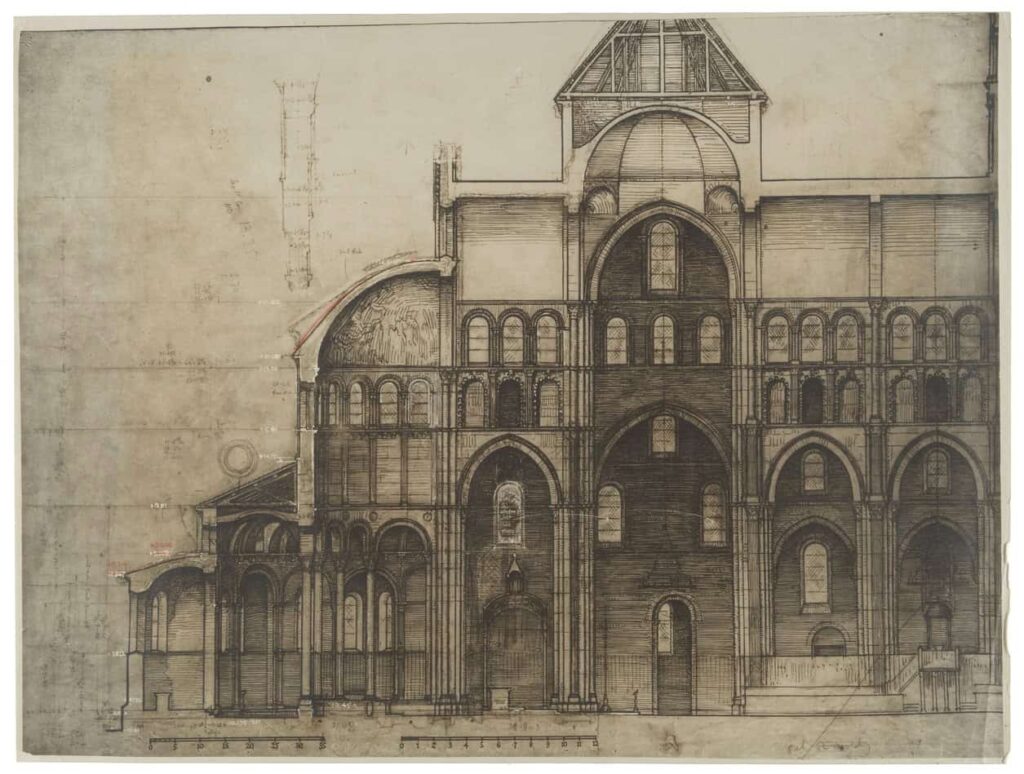

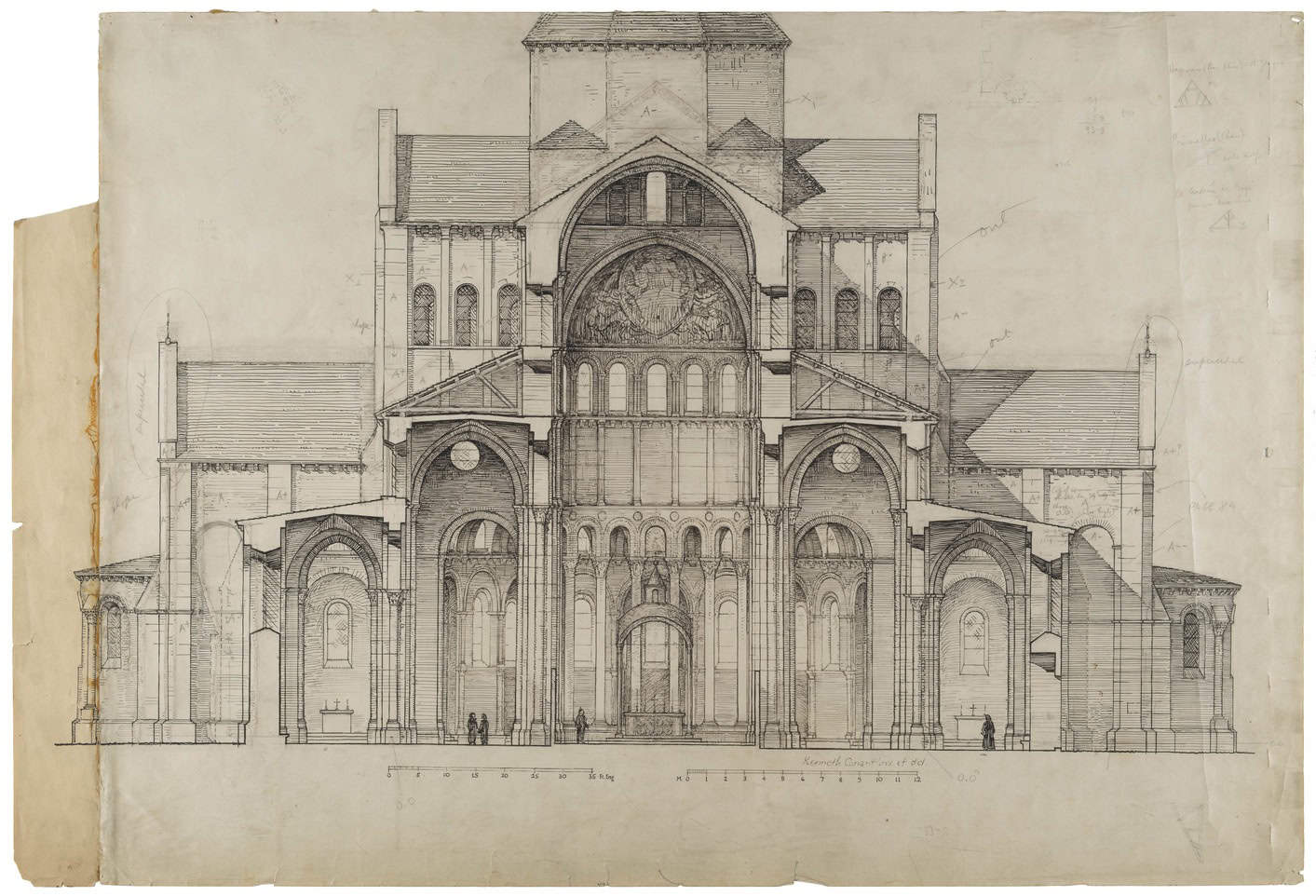

Conant’s training as both an architect and a historian and his experience with excavation enabled him to reconstitute the whole from the part. In this, his practice was radically different from that of his mentors Richardson, Warren and Porter, who were adept at picking out the significant or useful detail but less committed to identifying the unifying DNA of the whole – what Aristotle called the eîdos – the formal cause. It seems likely that this change is due not only to the development of architectural history as an academic field of research, but also because widespread loss of major historic monuments due to bombing in the two World Wars heightened awareness of the need to understand and record them as wholes. Conant re-created accurately dimensioned and structurally plausible elevations of Cluny from the available evidence. For example, figures 60 and 61 are highly finished measured drawings showing a half transverse section and nave wall elevation of the first nave bay. The drawing itself is byTurpin Bannister, Conant’s student at Harvard in the early 1940s and one of those who formed what became the Society of Architectural Historians in 1940. While elegant, Bannister’s drawings seem coldly precise. They record what was built so that the mind can understand it and perhaps even build it, with little or no appeal to the imagination. Conant also drew Cluny as a formal abstraction (fig. 62) but only to display the ideality of its form: his caption to this illustration in his book is “Le Plan de Cluny dans sa perfection.”[6] More typical of his drawings is fig. 63, a view of Cluny’s apse with its liturgical furnishings – the gospel and epistle ambos, tall branched paschal candlelabrum, ciborium over the high altar, the altar itself barely glimpsed through an opening in the choir screen, and rotae (wheel-shaped chandeliers), most (but not all) of which are documented – behind all this the apse hemicycle with columns figured capitals and the apse conch with Christ Enthroned partly painted and partly in mosaic. In the foreground a tomb (perhaps that of Pope Gelasius II, who died in 1119, recorded in that position outside the monks’ choir) and an altar. Conant represented not just what was there, but how it was lived and what effect it made on the spectator whereas Bannister’s hand recorded a lost architectural structure. Conant’s many views of the interior of Cluny as if seen from slightly different places in the building, as if experienced by a visitor, comprise an almost cinematic sequence (figs. 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71).

Kenneth Conant and Anna Strobel (b. 1925)

Labelled “Le plan de Cluny III dans sa perfection,” Cluny III in an ideal reconstructed plan as of 1120

Kenneth Conant

Reconstruction of Cluny III. Longitudinal section from the extreme east end chapel, through the ambulatory, apse, presbytery and south/east transept, and first two choir bays

Kenneth Conant

Reconstruction view of Cluny III. Transverse section through the choir bays between the east and west transepts, showing the exterior of the east transept, and a view into the interior of the presbytery, apse, and ambulatory, with liturgical furniture (high altar, choir screens, and corona), apse hemicycle, capitals, and fresco/mosaic in the apse conch

Kenneth Conant

Reconstruction view of Cluny III. View from the west transept of the altars before the monks’ choir enclosure, liturgical furniture in the choir (corona, pulpit, presbytery and high altar), with apse hemicycle columns, capitals and apse conch fresco/mosaic

Kenneth Conant

Reconstruction view of Cluny III. View from the seventh bay of the nave towards the apse

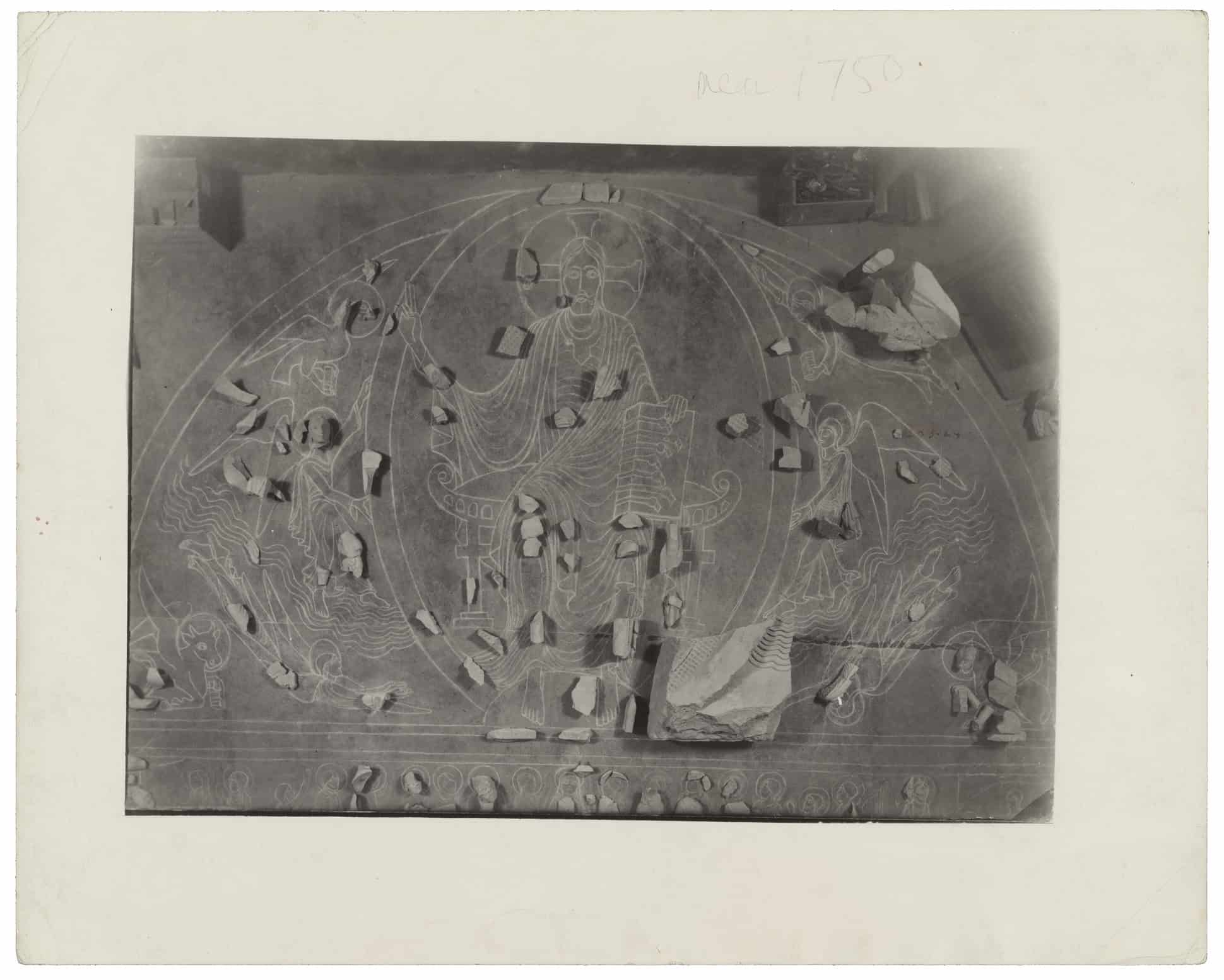

We highlight three especially spectacular examples of Conant’s skill in re-creating the whole from the part. All three show the transformation of the banal, the broken, and the inconsequential into the extraordinary, the amazing, and the beautiful. First, his large measured plan of the right half of the chevet of Cluny III (fig. 72) of which his full scale replica of the apse hemicycle at Cluny III in the Fogg Museum courtyard is the extrusion (fig. 73). What he understood from excavation and measurement, he then envisioned and realized in three dimensions. From the remains of Cluny’s footprint he erected the apse . That an architect would be able to deduce the elevation from the plan seems no great achievement unless, as was the case with Conant’s work with Cluny, the stylistic and structural assumptions of the original builders were unknown. Second, from the few broken sculpted fragments of the tympanum that had been blown up, Conant restituted its majestic sculpted and painted Maiestas Domini (figs. 74, 75). And third, perhaps the most remarkable and beautiful of all Conant’s efforts to envision Cluny is the large colored drawing of the church seen from the apse and showing the radiating chapels, ambulatory, and apse rising from the partial plan, the two transepts with their towers, and the towers of the west facade depicted ever more faintly as they recede in distance (fig. 76). Comparison with a print of almost the same view (fig. 77), which could have given him the idea of showing the whole by means of its high volumes, reveals the visionary, almost transcendental quality of Conant’s own representation. Truly, as he said shortly before his death, “Ah, Cluny … How wonderful … only paradise is more beautiful.”[7]

Kenneth Conant

Fogg Courtyard with Conant’s reconstruction of the apse hemicycle from the Abbey Church at Cluny made in the summer of 1933

The Cluny Collection

Exhibition: Envisioning Cluny: Kenneth Conant and Representations of Medieval Architecture, 1872–2025

Curator: Christine Smith, Robert C. and Marion K. Weinberg Professor of Architectural History

Collaborators: Matthew Cook, Digital Scholarship Programs Manager, Widener Library; Ines Zalduendo, Special Collections Curator at the Frances Loeb Library, M.Arch ’95

Animation: Clayton Scoble, Media Lab Director, Lamont Library

Assistants: Kian Hosseinnia, M.Arch ’24; Hayley Eaves, Ph.D Candidate

Exhibition Design: Dan Borelli, Director of Exhibitions, GSD, M.Des ’12

Online Exhibition Design: Ashleigh Brady, Archival Collections Website Editor, M.Arch ’26