The Plaster Casts of Cluny’s Apse Hemicycle Capitals

Soon after Conant began his excavation, in 1929, he commissioned plaster casts to be made of the eight capitals from the apse hemicycle (figs. 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85); the limestone originals are in the Musée Farinier in Cluny. These were executed by M. Lereculé from the then Palais de Trocadéro museum (now the Musée national des monuments français within the Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine) which had been established in 1879 by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc to house casts of French architectural and sculptural monuments. The casts, paid for by the Medieval Academy of America, the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, and private donations, were at first displayed in the courtyard of the Fogg Museum in 1930 (fig. 86).

Capital 1. Cast of a capital from the apse hemicycle of the abbey church at Cluny (Cluny III). Corinthianesque.

Capital 2. Cast of a capital from the apse hemicycle of the abbey church at Cluny (Cluny III). Figures on the angles perhaps representing the four seasons. 2) cloaked figure holding a book. Winter? 4) Figure in a short tunic with right arm raised, perhaps sowing seed. Spring? 6) Nude figure. Summer? 8) Figure with a large fur glove, perhaps a falconer. Fall?

Capital 3. Cast of a capital from the apse hemicycle of the abbey church at Cluny (Cluny III). Figures on the angles perhaps representing the four winds (north, south, east, and west). Only the lower parts of the figures remain on 2, 4, and 8. The subject of the capital is based on identifying what the figure at 6 holds as a bellows.

Capital 4. Cast of a capital from the apse hemicycle of the abbey church at Cluny (Cluny III). Four standing figures in hexagonal mandorlas represent the three Theological Virtues (Faith, Hope, and Charity) and one Cardinal Virtue, Justice. 1) only one foot remains, but the silhouette shows the figure holding something on a vertical cord, probably the scales of justice; 3) woman with an open coffer, Charity; 5) woman with bent legs and hands out, perhaps in prayer, Faith; and 7) woman holding a flowering baton, Hope.

Capital 5. Cast of a capital from the apse hemicycle of the abbey church at Cluny (Cluny III). Four standing figures in mandorlas, three of which have carved inscriptions, perhaps represent three Cardinal Virtues: 1)Prudence?; 3)Temperance?; 7)Fortitude; and one Liberal Art, 5) Grammar. These identifications do not match the inscriptions which are: 1) summer; 3)spring; 5) Prudence (this inscription was painted, not carved, and it disappeared in the process of making the casts); 7) Prudence.

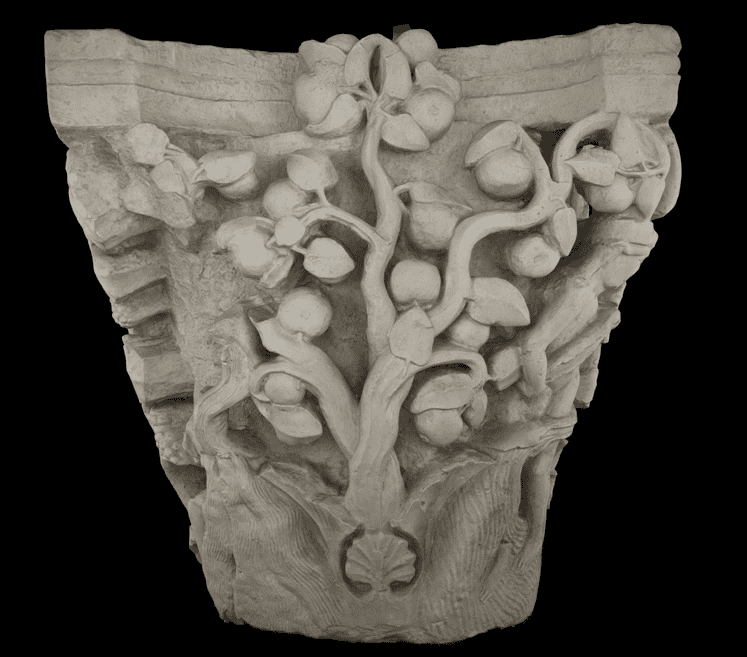

Capital 6. Cast of a capital from the apse hemicycle of the abbey church at Cluny (Cluny III). Four plants on the main faces- 1) apple tree; 3) fig tree? ; 5) almond tree? ; 7) grape vine—and the four Rivers of Paradise (Physon, Geon, Tigris, and Euphrates) on the angles(2, 4, 6,and 8).

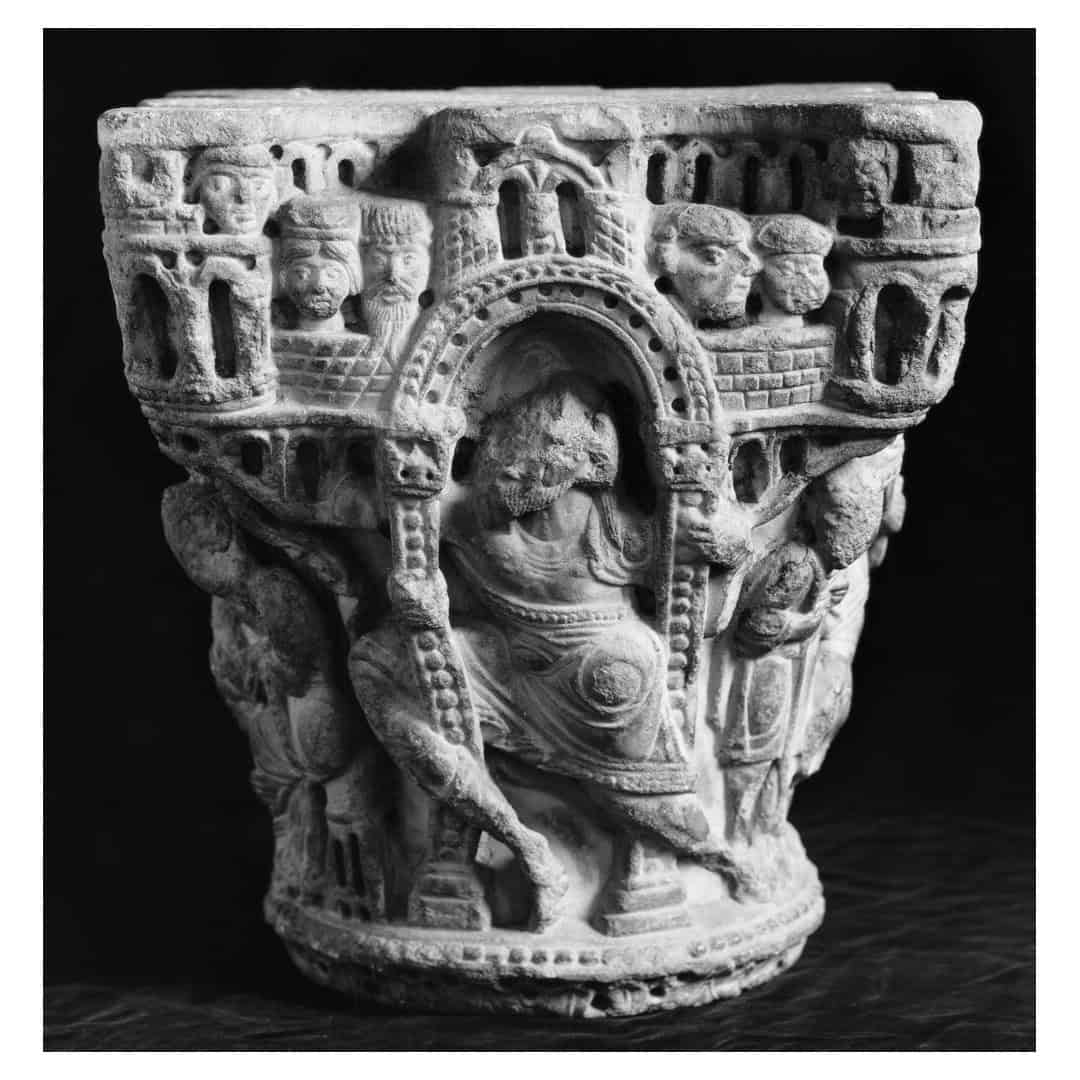

Capital 7. Cast of a capital from the apse hemicycle of the abbey church at Cluny (Cluny III). Figures in inscribed mandorlas represent the first four tones of plain chant. 1) seated man playing a lute (tone 1); 3) woman with cymbals or castanets (tone 2); 5) bearded man playing a stringed instrument (?) (tone 3); young man with a tintinnabulum (tone 4).

Capital 8. Cast of a capital from the apse hemicycle of the abbey church at Cluny (Cluny III), representing the last four tones of plain chant on the angles. Only the legs remain of the figures at 2 and 8: for these, Conant inserted plaster upper bodies. 4) is missing his head, but his instrument, a monochord, zither, or dulcimer, remains; 6) has a right arm (perhaps a horn or flute player?)but the rest of his torso is gone. The subject of the capital is identified by the inscriptions on a horizontal band.

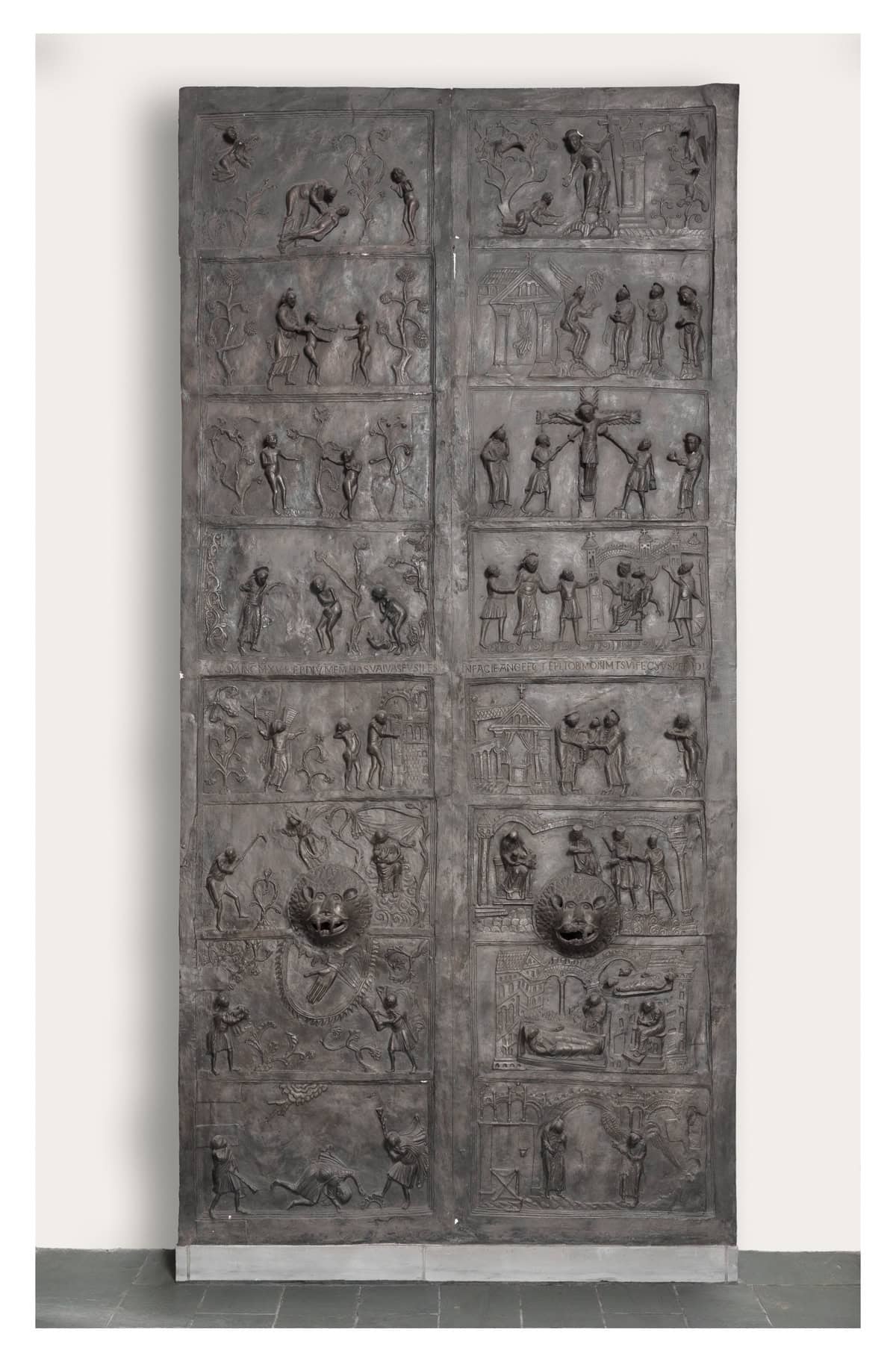

Both the Old Fogg Museum and Robinson Hall, the latter housing the architecture school from 1902 to 1972, already had significant collections of plaster casts, now dispersed, although some few pieces can still be seen at the GSD and elsewhere at Harvard (figs. 87, 88, 89). Drawing from casts was essential to the training of architects in the United States in the late-nineteenth to early-twentieth century. In this way they acquired facility working in various historical idioms while forming their taste based on models considered to be the best. And here, too, as we saw at the beginning what mattered was the telling part rather than the coherent whole. While in one sense the Cluny capital casts were quite ordinary additions to the Fogg display of great historical works, in other ways they were unusual, since most of the casts studied by American architecture students were of Greek and Roman antiquities or the Renaissance. The casts of panels from the Parthenon frieze acquired in 1895 for the opening of the Old Fogg Museum exemplify this (fig. 90) as do Richard Morris Hunt’s pair of classicizing griffons and an anthemion of cast stone for the museum’s roof and a pair of marble Classical or classicizing columns perhaps from Robinson Hall (figs. 91, 92, 93). Conant’s casts of the Cluny capitals were part of a new trend at Harvard to diversify the cultural contexts of the works of art displayed in Harvard museums both geographically and chronologically. Already in 1889, the Harvard Semitic Museum, now the Harvard Museum of the Ancient Near East, had been founded with artifacts collected for it by the Assyriologist David Gordon Lyon. And a Germanic Museum (later the Busch-Reisinger Museum) was established, again, much of the impetus coming from a Harvard professor, in this case, Kuno Francke. By 1903 casts of German medieval sculptures, donated by Kaiser Wilhelm II, could be seen at Harvard first in Rogers Hall but after 1921 in the present Busch Hall, the building having been designed by the German architect German Bestelmeyer but, because of the war, carried out by Herbert Langford Warren. This group included casts of the monumental Romanesque bronze doors and candlestick from Hildesheim (figs. 94, 95). The 1920s was also the time that Harvard began to acquire original works of western medieval sculpture. Photographs of the Old Fogg Museum show how plaster casts of the Parthenon frieze were exhibited together with French Romanesque capitals donated by Arthur Kingsley Porter and others (figs. 87, 96, 97). In 1933, while Conant’s plaster casts were on display at the Fogg, a major example of Romanesque sculpture was donated to the museum by the Spanish government through the offices of Arthur Kingsley Porter (fig. 98). This large columnar support from San Pelayo Antealtares in Compostela with its three standing apostles is an exceptionally fine example of Romanesque style.

Richard Morris Hunt (1827–1895), architect

Old Fogg Museum (Hunt Hall), 1893

Harvard Fine Arts Library, Special Collections, 1898L.00904 / 182 H267 6F(i)13

McKim, Mead, and White, architects

Robinson Hall, 1902 Black-and-white slide, 1904

Frances Loeb Library, Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 77485

McKim, Mead, and White, architects

Robinson Hall, 1902 Black-and-white slide, 1904

Frances Loeb Library, Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 77486

After Phidias (active 5th century BCE)

West Frieze, slab II of the Parthenon, Athens, Mounted Horsemen West Frieze, slab II of the Parthenon, Athens, Mounted Horsemen

original, Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Museum Purchase, 1895.25. Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Image courtesy of Anita Kan.

Richard Morris Hunt (1827-1895)

Anthemion (antefix) from the Old Fogg Museum (Hunt Hall)

Harvard University Graduate School of Design, HUCP1490

Two Classical or classicizing fluted columns

Marble, perhaps Bardiglio from Carrara, undated

Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Gebrüder Kusthardt

Replica of the Bernward Column (ca. 1020–1030) from the Church of St. Michael, Hildesheim, Germany, ca. 1900 Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College, BR30.34

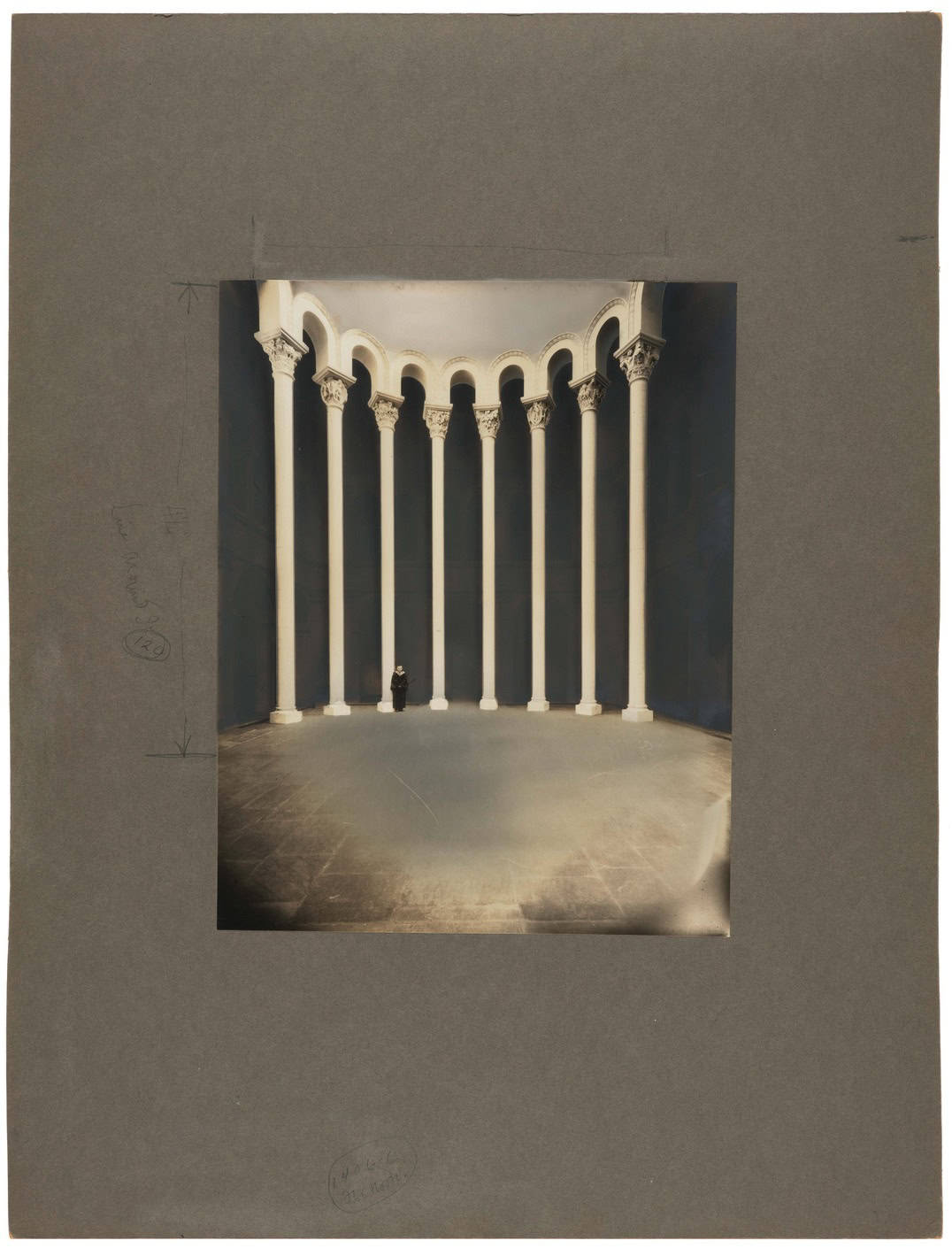

In the summer of 1933, the Boston Daily Transcript reported that the entire hemicycle of Cluny had been recreated in the recently-built Fogg Museum courtyard, an elegant space bounded by a loose copy of a Renaissance house in Montepulciano (fig. 99).[8] Envisioned by its designers Coolidge, Shepley, Bulfinch and Abbott as a setting for the contemplation of Classical/classicizing statues (or at least casts of such), one side of this Classically proportioned and culturally elite courtyard was masked by a replica of the Cluny hemicycle, a full 45 feet in height, its slender columnar supports flouting all rules of Classical proportions and its capitals peopled with a bizarre array of figures engaged in obscure activities (fig. 73). Even this challenge did not suffice for Conant: although the Cluny hemicycle was a screen through and behind which the Renaissance loggia was now seen, in Conant’s photograph the Fogg courtyard was entirely blacked out, leaving only the Cluny hemicycle. Conant himself, his academic regalia approximating the habit of a Benedictine monk, provided the scale (fig. 100). But if Conant hoped thereby to rival the hegemony of the Classical, he was disappointed when the casts of the Cluny capitals were sent to the Mount Holyoke College in 1936, rather than preserved at Harvard. In 2008 they returned to us and are now housed at the Graduate School of Design.

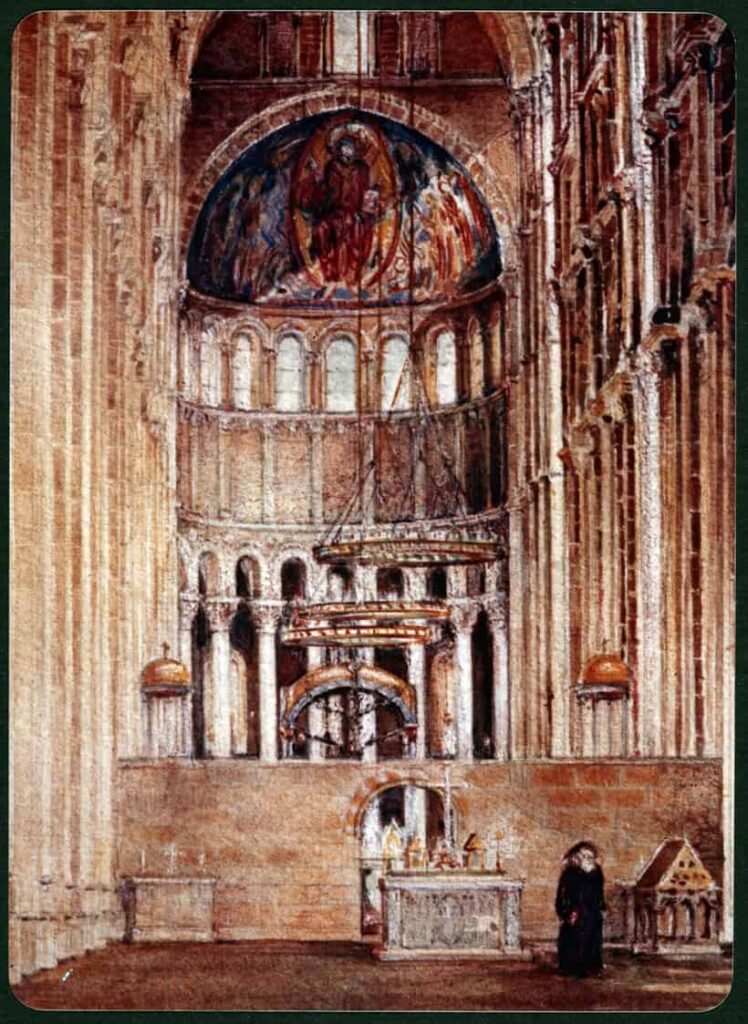

Eight capitals, made of local limestone, originally topped the columns of the apse hemicycle of Cluny III as recorded in drawings made before its dismantling in 1818. Six of the supporting columns were re-used sections of ancient Cipollino and Carrara marble columns, and two were of limestone painted to look like marble. The columns stood on plinths which were themselves tall, so that the capitals stood about 30 feet above the ambulatory pavement. While the visual effect was unclassically elongated – the height of the capital and columns together being eighteen times the diameter of the column – the apse hemicycle probably looked less vertical than Conant’s Fogg Museum reconstruction which, at 45 feet tall, equaled one-half the total height of Cluny’s apse.

The capital casts were displayed in the courtyard of the Fogg Museum from 1929 to 1934. They were first placed directly on the floor while Conant worked to establish their correct sequence and orientation, information essential for interpreting their meaning (fig. 86). All the capitals had fallen some 30 feet from their columnar supports to the ground in 1819 and are all damaged; the parts missing made, and make, their subjects difficult to identify. Conant’s photographic prints of the casts in negative suggest how, by heightening the contrast between dark and light areas, he enhanced their legibility (fig. 101). From the beginning, Conant intended to restore the missing parts of the capitals on the casts. In fact, he only completed one, Capital 8, as we can see comparing the original still in Cluny with the plaster cast as he displayed it at the Fogg Museum (figs. 102, 103).

Coolidge, Shepley, Bulfinch and Abbott

Architectural Rendering of the Courtyard of the Fogg Museum of Art, circa 1927

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College, 1927.47

Kenneth Conant

Fogg Courtyard with Conant’s reconstruction of the apse hemicycle from the Abbey Church at Cluny made in the summer of 1933

Kenneth Conant

Kenneth Conant with his reconstruction of the apse hemicycle of Cluny III in the Fogg Museum courtyard, 1934. The actual Fogg architecture is blacked out.

Capital 8 from the apse hemicycle of the Abbey Church at Cluny (Cluny III)

Photo courtesy of Sébastien Biay

Questions abound regarding these capitals and very little can be said with certainty. They must date sometime between 1095 (the date Conant preferred), when five main altars in Cluny’s apse were consecrated by Pope Urban II (the high and matutinal altars plus those in the three easternmost radiating chapels), and 1130-32 when the building was complete, and very likely before 1120 or even 1115. Although some scholars have suggested that the capitals were first installed and only later carved, Conant believed that they were certainly carved before being hoisted into place because the carving on one of the capitals extends beneath the impost block resting on it. The original sequence of the capitals is unknown, and Conant himself gave a different order to them in the Fogg reconstruction than he assigned in his 1968 publication. Seven of the eight capitals are carved with figures, some, but not all, of which can be identified, a task that might be facilitated if their relative placements were known. Another problem is establishing which is the front face of each, and therefore which eight faces were seen by a someone in the apse, for instance the priest celebrating Mass at the matutinal or high altar, and which by a spectator in the ambulatory. By extension, it isn’t clear what the intended audience for the capitals was and that further complicates efforts to interpret the iconographic program. If there was one.

All eight capitals are Corinthianesque in that they have (or had) volutes at the angles, an abacus, and a bell-shaped core. Most have acanthus leaves; some have a fleuron marking the center of the abacus. Three have figural decoration on the main faces; two have figures on the angles; two have figural ornament on both the main faces and the angles; and one has no figures. One capital places the figures on the main faces within hexagons, one uses almond shapes (mandorlas) to frame the figures, one shows trees and rivers with figures only on the angles; and two run horizontal bands around the middle of each capital over the figures on the faces or angles. In short, they do not share a common format and design. Our captions identify the location of the figures on the capitals by number: the main faces are 1,3,5, and 7 and the angles 2,4,6, and 8, using the system we adopted for the 3D digital models of the casts. We follow Neil Stratford’s authoritative catalogue for which is the front face of each and for their original sequence.

While some of the capitals have written inscriptions, others do not. One capital had a painted inscription that was erased by making the plaster cast and is recorded only by Conant. Because the capitals are damaged, many of the figures are broken. Consequently their poses aren’t clear and their attributes lost, again creating problems for identification. Further, since these are among the earliest Romanesque figural capitals few comparisons with related, earlier models are possible . In some cases their iconography seems to be based on manuscript texts and/or illustrations, but small scale sculptures have been suggested as sources for others. About their authorship, some scholars believe them to be by a single sculptor with an identifiable oeuvre, others think there were two masters, and some believe no such determinations can be made. The two most fundamental open questions about their iconography are 1) what does each capital represent; and 2) does the group have a common theme or subject. As Conant also concluded, there was probably never a coherent, unified iconographic program for the capitals. There are some quaternities: the four seasons (capital 2, fig. 79); the four winds (capital 3, fig. 80); the four rivers of paradise (capital 6, fig. 83); and the four cardinal virtues (capitals 4 and 5, figs. 81, 82). In addition, there are the three theological virtues (capital 4), one of the seven liberal arts (capital 4) and the eight tones of plainchant (capitals 7 and 8, figs. 84, 85). Conant suggested tha the subjects could be thought of in three groups: 1) human virtues, placed in the center of the apse (capitals 4 and 5); 2) capitals about nature ( capitals 2, 3, and 6); and 3) a group about divine praises (capitals 7 and 8).[9] That may be as close as we can get to a solution. As Stratford recognized, you have to consider the entire apse context of painted and mosaic apse conch, the black, white, and red marble and glass pavement, colored marble and marbleized columns.[10] One supposes the capitals, too, were originally painted. The capitals were integral parts of this splendid whole, much as we see it and Conant saw it in his mind’s eye (fig. 63).

Chronologically, this exhibition begins with Richardson’s photograph collection and his presentation drawings for Trinity Church, 1872 and ends with the 3D digital models created in 2022 of plaster casts made of twelfth-century capitals in 1929. Photographs, drawings, casts, digital images, and animations are all representational media by which architecture can be studied, taught, and designed. Not all these means were simultaneously available: we see how technology advanced and also how each medium fostered or hindered certain kinds of historical knowledge and creativity. This brings to the fore thoughts about the use of “precedents” for architectural design and in architectural education. It was my intention to celebrate the continuity but also the progress in the study and teaching of architectural history at the Graduate School of Design, especially through the career of my predecessor, Kenneth Conant. The exhibition’s narrative is told entirely through visual materials from repositories at Harvard University, most of which I have used in my classes.

Christine Smith

Robert C. and Marion K. Weinberg Professor of Architectural History, Graduate School of Design

footnotes

[1] P. xxv.

[2] See especially, Trachtenberg, M., Building in Time. From Giotto to Alberti and Modern Oblivion, New Haven, 2010

[3] Conant, K., “A Replica of the Arcade of the Apse at Cluny, ”Bulletin of the Fogg Art Museum, 3.1, 1933, pp. 5-8, p.6

[4] A still controversial matter. Most recently Anne Baud argued that, contrary to Conant, construction began in the south arm of the major transept and proceeded eastward in horizontal slices. “Archaeology and the Abbey of Cluny, in Bruce, S.G., and Vanderputten, S., A Companion to the Abbey of Cluny in the Middle Ages, Leiden, 2021, pp. 146-72, p. 162.

[5] See Armi, C. Edson, “The Context of the Nave Elevation of Cluny III,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 69.3, 2010, 321-51

[6] Conant, K., Cluny: les églises et la maison du chef d’ordre, Mâcon, (Mediaeval Academy of America) no. 77.), 1968, fig. 67

[7] Shortly before his death Conant was asked if the rainy weather reminded him of Cluny. He replied with that quotation. In P. Fergusson, Necrology — Kenneth John Conant (1895-1984), Gesta, 29, 1985, pp. 87-88, p. 88.

[8] Cochrane, A.F., “Tall Columns of Cluny at Fogg Museum,” Boston Evening Transcript, Saturday, August 5, 1933, p. 8

[9] Conant, Kenneth J., “The Iconography and Sequence of the Ambulatory Capitals at Cluny, Speculum, 5, 1930, pp. 278-87, p. 285.

[10] Steatford, N., “The Apse Capitals of Cluny III,” in Studies in Burgundian Romanesque Sculpture, London, 1998, pp. 77-90, p. 82.\

The Cluny Collection

Exhibition: Envisioning Cluny: Kenneth Conant and Representations of Medieval Architecture, 1872–2025

Curator: Christine Smith, Robert C. and Marion K. Weinberg Professor of Architectural History

Collaborators: Matthew Cook, Digital Scholarship Programs Manager, Widener Library; Ines Zalduendo, Special Collections Curator at the Frances Loeb Library, M.Arch ’95

Animation: Clayton Scoble, Media Lab Director, Lamont Library

Assistants: Kian Hosseinnia, M.Arch ’24; Hayley Eaves, Ph.D Candidate

Exhibition Design: Dan Borelli, Director of Exhibitions, GSD, M.Des ’12

Online Exhibition Design: Ashleigh Brady, Archival Collections Website Editor, M.Arch ’26